Decreased risk of chronic fatigue syndrome following influenza vaccine: a 20-year population-based retrospective study

Chang, Hsun; Yao, Wei-Cheng; Yu, Teng-Shun; Lin, Heng-Jun; Tsai, Fuu-Jen; Ho, Shinn-Ying; Kuo, Chien-Feng; Tsai, Shin-Yi

BACKGROUND

Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (CFS) is a debilitating condition often follows infections, including influenza. Influenza frequently results in fatigue during the acute stage. However, the data regarding the association of influenza, vaccine and CFS is scarce. Thus, this study aims to investigate whether influenza increases the risk of developing CFS and examine the impact of influenza vaccination and severity of influenza on this risk.

METHODS

We conducted a national, population-based cohort study, using data from the National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD) of Taiwan, which identified 309,692 patients aged 20 years or older who were newly diagnosed with influenza between 2000 and 2019. An equal number of participants without influenza were also identified. Both groups were followed up until the end of CFS diagnoses. Cox proportional hazards regression analysis was used to calculate adjusted hazard ratios(aHRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for CFS as associated with influenza, adjusting for demographic factors and comorbidities. We also evaluated the effects of influenza vaccination and severe influenza.

RESULTS

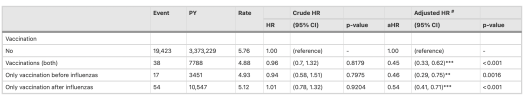

After propensity matching, each cohort comprised 309,692 patients. Over an average follow-up period of approximately 12 years, influenza patients exhibited a significantly increased risk of developing CFS compared to matched controls (aHR = 1.51; 95% CI: 1.48–1.55; p < 0.001). The increased risk of CFS among patients with influenza was consistent across all age groups and both sexes, with the most pronounced elevation observed in older individuals. Patients who experienced severe influenza, as indicated by the need for mechanical ventilation, exhibited a significantly higher risk of developing CFS compared to those who did not require ventilatory support. In contrast, influenza vaccination was associated with a reduced risk of developing CFS. Patients who received the influenza vaccine—either before or following their influenza episode—exhibited a lower incidence of CFS than those who remained unvaccinated. The protective effect of vaccination was not evident in patients with severe influenza requiring ventilation.

CONCLUSIONS

Influenza infection is associated with an increased risk of developing CFS. These findings suggest that preventing influenza and mitigating its severity, such as through vaccination, could reduce the burden of CFS in at-risk populations.

Link | PDF | Journal of Translational Medicine [Open Access]

Chang, Hsun; Yao, Wei-Cheng; Yu, Teng-Shun; Lin, Heng-Jun; Tsai, Fuu-Jen; Ho, Shinn-Ying; Kuo, Chien-Feng; Tsai, Shin-Yi

BACKGROUND

Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (CFS) is a debilitating condition often follows infections, including influenza. Influenza frequently results in fatigue during the acute stage. However, the data regarding the association of influenza, vaccine and CFS is scarce. Thus, this study aims to investigate whether influenza increases the risk of developing CFS and examine the impact of influenza vaccination and severity of influenza on this risk.

METHODS

We conducted a national, population-based cohort study, using data from the National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD) of Taiwan, which identified 309,692 patients aged 20 years or older who were newly diagnosed with influenza between 2000 and 2019. An equal number of participants without influenza were also identified. Both groups were followed up until the end of CFS diagnoses. Cox proportional hazards regression analysis was used to calculate adjusted hazard ratios(aHRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for CFS as associated with influenza, adjusting for demographic factors and comorbidities. We also evaluated the effects of influenza vaccination and severe influenza.

RESULTS

After propensity matching, each cohort comprised 309,692 patients. Over an average follow-up period of approximately 12 years, influenza patients exhibited a significantly increased risk of developing CFS compared to matched controls (aHR = 1.51; 95% CI: 1.48–1.55; p < 0.001). The increased risk of CFS among patients with influenza was consistent across all age groups and both sexes, with the most pronounced elevation observed in older individuals. Patients who experienced severe influenza, as indicated by the need for mechanical ventilation, exhibited a significantly higher risk of developing CFS compared to those who did not require ventilatory support. In contrast, influenza vaccination was associated with a reduced risk of developing CFS. Patients who received the influenza vaccine—either before or following their influenza episode—exhibited a lower incidence of CFS than those who remained unvaccinated. The protective effect of vaccination was not evident in patients with severe influenza requiring ventilation.

CONCLUSIONS

Influenza infection is associated with an increased risk of developing CFS. These findings suggest that preventing influenza and mitigating its severity, such as through vaccination, could reduce the burden of CFS in at-risk populations.

Link | PDF | Journal of Translational Medicine [Open Access]