Symptomatic Trends and Time to Recovery for Long COVID Patients Infected During the Omicron Phase

BACKGROUND

Since the pathophysiology of long COVID is not yet fully understood, there are no specific methods for its treatment; however, its individual symptoms can currently be treated. Long COVID is characterized by symptoms that persist at least 2 to 3 months after contracting COVID-19, although it is difficult to predict how long such symptoms may persist.

METHODS

In the present study, 774 patients who first visited our outpatient clinic during the Omicron period from February 2022 to October 2024 were divided into two groups: the early recovery (ER) group (370 cases; 47.8%), who recovered in less than 180 days (median 33 days), and the persistent-symptom (PS) group (404 cases; 52.2%), who had symptoms that persisted for more than 180 days (median 437 days). The differences in clinical characteristics between these two groups were evaluated.

RESULTS

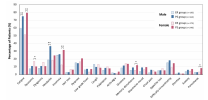

Although the median age of the two groups did not significantly differ (40 and 42 in ER and PS groups, respectively), the ratio of female patients was significantly higher in the PS group than the ER group (59.4% vs. 47.3%). There were no significant differences between the two groups in terms of the period after infection, habits, BMI, severity of COVID-19, and vaccination history. Notably, at the first visit, female patients in the PS group had a significantly higher rate of complaints of fatigue, insomnia, memory disturbance, and paresthesia, while male patients in the PS group showed significantly higher rates of fatigue and headache complaints. Patients with more than three symptoms at the first visit were predominant in the PS groups in both genders. Notably, one to two symptoms were predominant in the male ER group, while two to three symptoms were mostly reported in the female PS group. Moreover, the patients in the PS group had significantly higher scores for physical and mental fatigue and for depressive symptoms.

CONCLUSIONS

Collectively, these results suggest that long-lasting long COVID is related to the number of symptoms and presents gender-dependent differences.

Web | PDF | Journal of Clinical Medicine | Open Access

Akiyama, Hiroshi; Sakurada, Yasue; Honda, Hiroyuki; Matsuda, Yui; Otsuka, Yuki; Tokumasu, Kazuki; Nakano, Yasuhiro; Takase, Ryosuke; Omura, Daisuke; Ueda, Keigo; Otsuka, Fumio

BACKGROUND

Since the pathophysiology of long COVID is not yet fully understood, there are no specific methods for its treatment; however, its individual symptoms can currently be treated. Long COVID is characterized by symptoms that persist at least 2 to 3 months after contracting COVID-19, although it is difficult to predict how long such symptoms may persist.

METHODS

In the present study, 774 patients who first visited our outpatient clinic during the Omicron period from February 2022 to October 2024 were divided into two groups: the early recovery (ER) group (370 cases; 47.8%), who recovered in less than 180 days (median 33 days), and the persistent-symptom (PS) group (404 cases; 52.2%), who had symptoms that persisted for more than 180 days (median 437 days). The differences in clinical characteristics between these two groups were evaluated.

RESULTS

Although the median age of the two groups did not significantly differ (40 and 42 in ER and PS groups, respectively), the ratio of female patients was significantly higher in the PS group than the ER group (59.4% vs. 47.3%). There were no significant differences between the two groups in terms of the period after infection, habits, BMI, severity of COVID-19, and vaccination history. Notably, at the first visit, female patients in the PS group had a significantly higher rate of complaints of fatigue, insomnia, memory disturbance, and paresthesia, while male patients in the PS group showed significantly higher rates of fatigue and headache complaints. Patients with more than three symptoms at the first visit were predominant in the PS groups in both genders. Notably, one to two symptoms were predominant in the male ER group, while two to three symptoms were mostly reported in the female PS group. Moreover, the patients in the PS group had significantly higher scores for physical and mental fatigue and for depressive symptoms.

CONCLUSIONS

Collectively, these results suggest that long-lasting long COVID is related to the number of symptoms and presents gender-dependent differences.

Web | PDF | Journal of Clinical Medicine | Open Access