Persistent fatigue as a model for CFS

Sorry about the length of this: would have been shorter if I'd had more energy

Concerns about this research have already been covered well: Pariente's strong belief that ME/CFS is a psychosocial illness; that this isn't a study of ME/CFS itself, but a proposed model; that it only considers fatigue and not PEM, yet doesn't consider this to be a model of other fatiguing illnesses. Not to mention that the model is is a dead duck because new treatments for hepatitis C means that interferon alpha therapy is now obsolete.

Even so, as

@Sid has already said, there are reasons to give the study serious consideration.

One is that the model might just reveal something useful about a hit-and-run scenario where ME/CFS starts as a result of a one off infection or other immune insult. Many researchers consider this scenario quite possible and the results of the new study tally with those of the original Dubbo study. The other reason is that if this is a decent model for CFS, it provides both evidence for a biomedical explanation and evidence against a psychosocial one. This was a Bake off between psychosocial and biomedical explanations of persistent fatigue, and it wasn't even close.

___

The possible relevance of the model

The problem with ME/CFS is that cases aren't diagnosed until long after the initial infection has resolved and very often there are few biological abnormalities to be seen. And while there is a reasonable understanding of the biology behind other illnesses with substantial levels of fatigue, including cancer, MS and rheumatoid arthritis, we are still largely in the dark about ME/CFS. This model has (or had) the potential shed some light on things.

For instance, although researchers often report cytokine differences between ME/CFS patients and healthy controls, these are quite small and are not really sufficient to explain an illness of this severity. Is the finding just a secondary association? What would really help is a prospective approach, studying the illness as it develops because changes that happened as the illness sets in are much more likely to be causal than ones that are simply associated with a long-standing disease.

The best example of this prospective approach is the

Dubbo study of post-infectious CFS set in the Australian outback. This study found that what predicted CFS at six months following three different acute infections (glandular fever/EBV, Ross River virus and Q fever) was the severity of the initial illness, and not by demographic or psychosocial factors. However, six months after the initial infection, cytokine levels were back to normal in both the ME/CFS and recovered groups. The study authors suggested there could be a hit-and-run mechanism to CFS where an initial severe illness led to long-term changes in biology (I think they were the first to suggest the brain's microglia were playing a role) that sustained ME/CFS.

The key thing about Dubbo is that it followed new cases from the initial infection through to developing of CFS. Pariente's work had aimed to create a more convenient model for studying the onset of fatigue following an immune insult. It was based on the treatment of hepatitis C patients with interferon alpha which was known to cause persistent fatigue in some after the interferon therapy had stopped. Sure, this only looked at fatigue, and fatigue levels were substantially less than those seen in ME/CFS but it could be reveal something useful.

Jarred Younger is key proponent of the view that an initial immune insults leads to primed microglia in the brain and that is responsible for ME/CFS, so this is relevant to an important mainstream theory. (Normally, an infection leads to an increase in cytokines e.g interferon-alpha, which in turn activate microglia, leading to the sickness response inc fatigue, malaise and problems concentrating. This should unwind when the infection ends but might not in mecfs.) In 2014, a Japanese study found neuroinflammation - microglial activation) in ME/CFS patients — work that is now been followed up by Maureen Henson, Michael VanElzakker and Ron Davies — as well as Younger himself.

The study, its results and how they fit with Dubbo

The study uses interferon alpha treatment of hepatitis C patients, which dramatically reduces the level of virus, but also causes substantial fatigue during therapy. For most patients, at the end of the study fatigue levels fall back to normal, healthy levels "resolved fatigue, RF" (unsurprising, since the level of hepatitis C has been brought under control). But around one third of those who have treatment experience

persistent fatigue, PF, after the treatment has ended, and they are the focus of this study. Its strength is that researchers can measure features of patients both before and during treatment to see if they predict or explain which patients go on to develop persistent fatigue.

Results

What they found was that those who developed persistent fatigue had higher fatigue levels during treatment, higher levels of pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-6 and the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10, and had more treatment sessions or sessions over a longer period than patients who did not develop persistent fatigue. In contrast, there were no differences between the groups in demographics or what Pariente described as "classical psychosocial" factors. In other words, the research looked at both biological and psychosocial factors and discovered it was biological factors that predicted persistent fatigue.

Pariente said that having treatment spread over a longer period, and also having more sessions in total was associated with persistent fatigue.

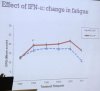

Fatigue results (note that fatigue levels are much lower than activity seen in ME/CFS):

View attachment 4385

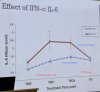

Cytokine results:

View attachment 4386

It is a little strange that both pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines where elevated; Pariente suggested that the increase in the anti-inflammatory IL -10 might be the body trying to dampen down inflammation. Interferon alpha itself is strongly pro-inflammatory and is other work on this treatment shows that interferon alpha does ramp up inflammation in the body.

However, there was no difference between the persistent fatigue group and the result fatigue group at six months.

Vs Dubbo

The Dubbo results were not so different. Baseline psychosocial factors did not significantly predict developing CFS, but the severity of the initial illness did, and there was some evidence of a stronger proinflammatory cytokine response during the infection in those that went on to develop CFS.

For any given infectious agent, much of the difference in illness severity betweeen patients is down to their immune response: a stronger immune response makes you feel sicker. So both Dubbo (severe illness) and the interferon alpha treatment (the length of inteferon treatment and number of sessions, level of other cytokines, and fatigue) indicate the strength of immune response is key. Pariente suggested that it might be that having longer or more severe immune activation during the initial illness could be in an important factor risk factor for ME/CFS.

Pariente's view of the future

At the end of the presentation he made the assumption that the model was married to ME/CFS and appeared to be pursuing a largely biological line of enquiry:

What is abnormal about those who develop chronic fatigue syndrome, why did they have the stronger immune response?

He speculated that this could be down to priorinfection, within the womb or during early childhood. He felt that might sensitise the immune system and subsequently, when someone has an infection (or psychosocial issues!) That might trigger an abnormally large immune response and lead to ME/CFS. Pariente was still very interested in the role of psychosocial factors, but that was speculation — the evidence was own study was about the importance of biomedical factors rather than psychosocial ones.

Given that is hepatitis C model is now redundant, Pariente suggested that what was needed was defined other groups persistent fatigue were similar prospective approach could be used.

Dubbo Mark 2?

I would suggest that better still would be a Dubbo 2.0 study, prospectively following new cases of glandular fever. There are no shortage of glandular fever cases in the UK and this approach has a huge advantage of allowing the study of ME/CFS as it develops. The drawback is that you don't have data at baseline, before the infection strikes, and you don't have the convenience of patients regularly attending hospital treatment, when blood samples et cetera can be taken.