MeSci

Senior Member (Voting Rights)

I wasn't sure where to put this as it was in a Psychology magazine but it looked more scientific than that.

Source: Frontiers in Psychology

Preprint

Date: July 26, 2018

URL:

https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01468/abstract

Visual aspects of reading performance in Myalgic Encephalomyelitis (ME)

----------------------------------------------------------

Rachel Wilson, Kevin B. Paterson, Victoria A. McGowan, Claire Hutchinson(*)

- University of Leicester, United Kingdom

* Corresponding author

Received: 28 Nov 2017

Accepted: 26 Jul 2018

Abstract

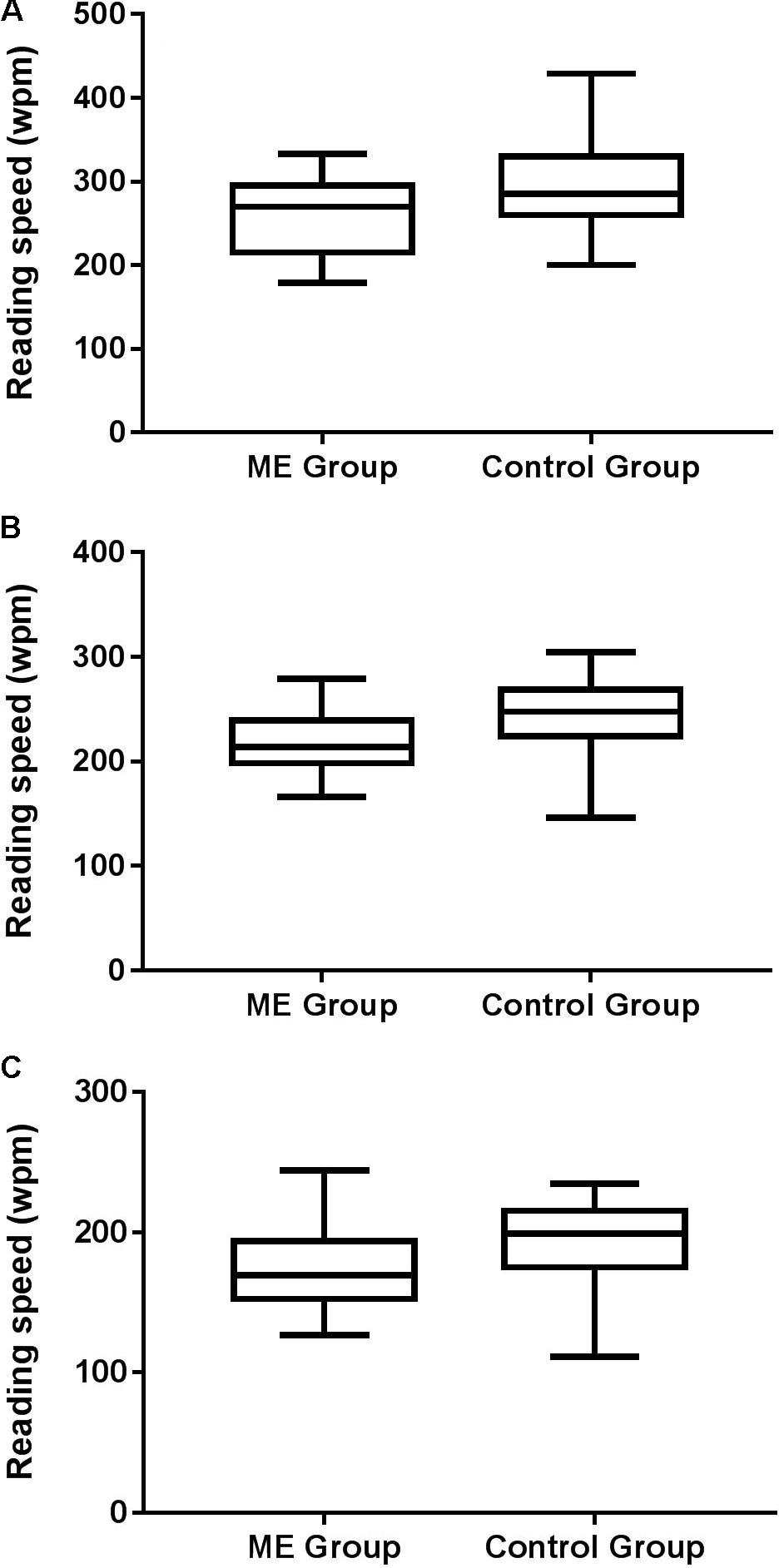

People with Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS) report vision-related reading difficulty, although this has not been demonstrated objectively. Accordingly, we assessed reading speed and acuity, including crowded acuity and acuity for isolated words using standardised tests of reading and vision, in 27 ME/CFS patients and matched controls. We found that the ME/CFS group exhibited slower maximum reading speed, and had poorer crowded acuity than controls.

Moreover, crowded acuity was significantly associated with maximum reading speed, indicating that patients who were more susceptible to visual crowding read more slowly. These findings suggest vision-related reading difficulty belongs to a class of measureable symptoms for ME/CFS patients.

Keywords: Myalgic encephalomyelitis, chronic fatigue syndrome, Reading Speed, Reading acuity, Visual Acuity, crowded acuity

Source: Frontiers in Psychology

Preprint

Date: July 26, 2018

URL:

https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01468/abstract

Visual aspects of reading performance in Myalgic Encephalomyelitis (ME)

----------------------------------------------------------

Rachel Wilson, Kevin B. Paterson, Victoria A. McGowan, Claire Hutchinson(*)

- University of Leicester, United Kingdom

* Corresponding author

Received: 28 Nov 2017

Accepted: 26 Jul 2018

Abstract

People with Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS) report vision-related reading difficulty, although this has not been demonstrated objectively. Accordingly, we assessed reading speed and acuity, including crowded acuity and acuity for isolated words using standardised tests of reading and vision, in 27 ME/CFS patients and matched controls. We found that the ME/CFS group exhibited slower maximum reading speed, and had poorer crowded acuity than controls.

Moreover, crowded acuity was significantly associated with maximum reading speed, indicating that patients who were more susceptible to visual crowding read more slowly. These findings suggest vision-related reading difficulty belongs to a class of measureable symptoms for ME/CFS patients.

Keywords: Myalgic encephalomyelitis, chronic fatigue syndrome, Reading Speed, Reading acuity, Visual Acuity, crowded acuity