A continuation on my above posts. I’ll try to explain a bit of the process I went through and the theory then how I decided to look at the number clusters that I did.

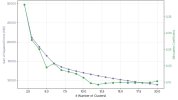

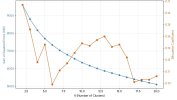

In clustering theory, there's both the silhouette (a measure of cohesion, or how similar a data point is to other data points in its cluster and how different it is to other clusters) and the elbow method, here using Sum of Squared Errors (where you plot the in cluster variation of data points and find a point where adding more clusters doesn’t reduce variation).

That’s what these charts show in Silhouette Coefficient and SSE. So as I understand we should look for a point where the first measure is high and the second is starting to reduce less, so you’re getting coherent clusters and diminishing returns for adding more clusters.

The scripts also create heat maps which allow you to visually assess groups of genes, and show dendrograms (diagrams which illustrate the arrangement of the clusters). As well as plots of gene and cluster silhouette values.

Why cluster at all? The idea is if genes seem to have similar patterns of expression in different tissues, it's plausible that they're more likely to be involved in the same pathways than genes which have different patterns.

Why not cluster into 2 groups, that seems to have a high silhouette? I think this largely just separates things into brain and non-brain, which doesn’t tell us much. We need a greater number of clusters to tell us more.

So then the final step once you have these clusters, these different lists of related or potentially related or co-expressed genes, is to use some of the tools like STRING DB or Enrichr to identify what they may be doing.

These take lists of genes and query big databases and give you an idea of what protein-protein interactions, biological mechanisms, pathways or diseases these gene groups are involved in.

And as far as I know, an advantage of doing this with the clusters rather than the whole gene set is that you’re increasing specificity. Rather than saying, 'Okay, what processes are these 259 genes involved in?' You're saying, 'What processes are these five or 10 or 20 genes involved in?' So you can be much more specific and get a better and hopefully more statistically significant answer.

And these databases, these queries, one of the nice things is they return measures of statistical significance. So they return p-values and false discovery rates. So then the idea is for each cluster, we get a report of what genes are in that cluster and the results from these databases and the statistics for everything to aid interpretation.

I generate a report at the end of this which includes the more statistically significant results from the queries. But there are also links to the complete data from the analysis for people who need it.

Some more background and references

en.wikipedia.org

en.wikipedia.org

en.wikipedia.org

Gene Ontology overview The Gene Ontology (GO) is a structured, standardized representation of biological knowledge. GO describes concepts (also known as terms, or formally, classes) that are connected to each other via formally defined relations. The GO is designed to be species-agnostic to...

geneontology.org