I've drifted at high speed through this rather dense article that seems to use a lot of words to say that MUS is a problem, that it's an anomaly in biomedicine because it's symptoms without signs, that this is solved by passing it over to psychiatry who can't explain it either, but that's OK so long as they can help the patients.

Is this another version of the Sharpe/Grecko 'illness without disease' paper? I'm confused. Here's my attempt at picking out some relevant bits. I might have completely missed the point.

Here's my version with some quotes.

Start by assuming MUS is a real category worth researching and claim there's lots of research happening:

Yet medically unexplained symptoms are continually and increasingly the object of clinical research. Paradoxically, then, despite being first partially then completely excluded from the formalized medical classification systems, the MUS category is increasingly enlisted in medical research and is thus steadily becoming a central medical category; it is pushed to the fringe yet drawn towards the centre of medical science.

Then waffle a lot about classification and anomalies to confuse your reader and sound erudite, then do a limited literature search and discover most of is it in psychosomatic journals:

Judging by the publication rates in the journals sampled, the MUS category is used mostly in the context of psychiatric and primary care research (most frequently in the former) (177/60), though MUS is invoked in psychosomatic contexts more often than in psychiatry in general

Draw some conclusions from the research you've sampled:

Various definitions of MUS listed, all summed up as

...premised on the co-occurrence of present symptoms and absent signs. ...

MUS may thus be characterized as anomalies constituted by their lack of fit with scientific biomedicine, by their violation of expectations induced by the biomedical paradigm. ...

...discordance’ between what the patient says and what the doctor can find must thus be accounted for.

Waffle some more about categories and paradigms:

The analysis has demonstrated how MUS is constituted as a ‘junk drawer category’, and how this category is managed in medical research. First, I have shown that the core criterion of MUS as a category is the co-occurrence of present somatic symptoms and absent somatic signs of disease, and that, fundamentally, this criterion is an expression that MUS violate expectations induced by the biomedical paradigm. Biomedicine as epistemic convention is therefore causally implicated in making symptoms anomalous and this ‘paradigm-induced’ anomalous character is what constitutes MUS as a category. In other words, the junk drawer is constituted as a contravention of the existing order. The majority of articles, however, hide the constitutive role of biomedicine, making the core criterion an ontological fact about the symptoms, rather than an epistemic fact about the beliefs and practices of the profession. Thus, the nature of the MUS category as a junk drawer is concealed.

And conclude that MUS is only anomalous if we try to explain it with biomedicine.

The implication being that biomedicine may be the wrong model, so bring in psychiatry instead and talk about the problem that patients don't like this?

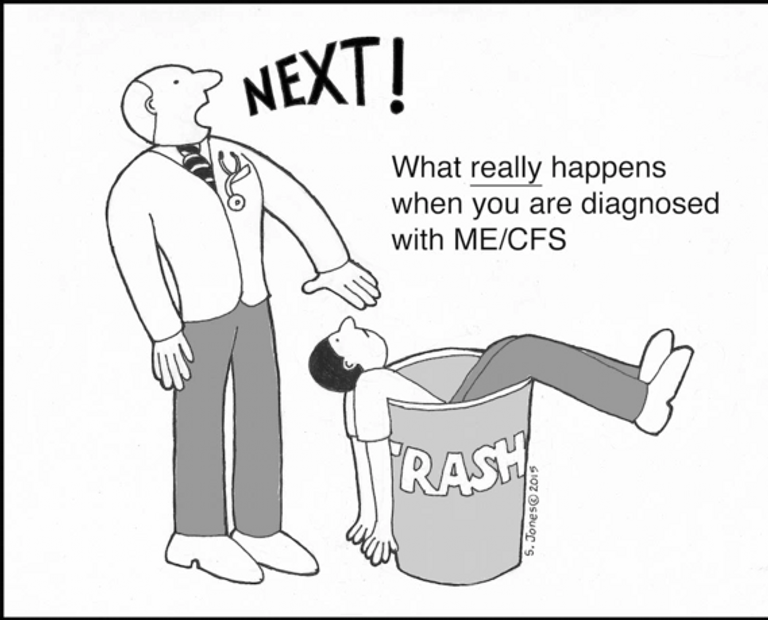

Regarding puzzle solving, historians of science and others suggest that when anomalous phenomena are not simply ignored or discarded, scientists will typically try somehow to make them fit in by making slight adjustments or creating new categories to the established order, or by proposing rule-exceptions that dampen or remove the anomalous character. These strategies are called ‘monster-adjustment’ (Bloor, 1978). There are strong indications of a move towards such strategies in the sample, in the form of assumptions that unexplained physical symptoms are really symptoms of mental distress (e.g. Jutel, 2010). Such assumptions are criticized in the sample (e.g. 5-3) but not nearly as often as they are taken for granted. They come to the fore, for instance, in the conviction that psychiatric therapy is appropriate for but hampered by uncooperative patients (e.g. 6-5; 11-7) or in the fact that only two articles in the sample actually investigate new hypotheses that MUS have somatic causes (7-9; 8-5). As indicated in the analysis, the connection with somatization is one way this assumption seeps through. Other ways are through concepts that carry similar psychogenic assumptions – such as ‘alexithymia’ (2-3), ‘illness perceptions’ (9-10), and ‘somatovisceral illusions’ (1-16), each indicating that the patients have misunderstood the nature of their symptoms. As such, psychogenic assumptions are part of the biomedical doxa and the commitment to make MUS ‘fit in’. They may be interpreted as a form of monster-adjustment, pushing for the resolution of the anomalous character of present symptoms without signs. This interpretation of MUS as caused by a misunderstanding on the patient’s part has been criticized by some social scientists as a form of blame-shifting (e.g. Horton-Salway, 2002; Jutel, 2010). Others have been more cautious.

And trick patients into accepting psych treatment in order to show them it works?

Greco (2012: 2365) warns against any knee-jerk criticism of psychogenic assumptions by social scientists. She argues that the medical profession might be right to treat MUS as psychogenic and that the question must be settled empirically. Inasmuch as ‘right’ indicates that it could work, I agree. However, from what evidence there is, it does not seem to do the trick: An important context where psychogenic assumptions are expressed is when researchers complain that Rasmussen 19 patients reject psychiatric treatment (e.g. 6-5; 11-7). Undeterred, researchers have experimented with the reframing of psychiatric treatment as somatic treatment, trying to get patients into disguised psychiatric treatment (e.g. 8-8, 2013: 300). In one study, this strategy is unashamedly presented as ‘a Trojan horse’ (6-6, 2011: 3) – without considering the risk that patients will learn to fear the GPs when they come bearing ‘therapeutic gifts’.

And if that doesn't work, keep experimenting?

Somatization in its varieties has yet to succeed as a monster-adjusting strategy. Moreover, due to recent changes whereby all SD diagnoses have been ejected from formal classifications (American Psychiatric Association, 2013), the strategy might have to change. But that is the beauty of a ‘junk drawer category’: They can try again later.

And perhaps try harder to refine the definition of MUS to make a more homogeneous research cohort?

Formalizing a set of criteria, for instance relating to symptom count, impact and persistence, or the frequency of attendance, would probably enable researchers to study a more homogenous patient group than current practices allow for. However, standardized criteria do not necessarily make classification homogenous, as they must nevertheless be interpreted and applied in the course of situated practice

But what if you disagree about what is explained and what is unexplained?

Moreover, there are reasons to believe that what I call the core criterion is itself a major source of variation: studies indicate that even when criteria are formalized and shared, doctors disagree about where to draw the line between the explained and unexplained (e.g. Creed and Barsky, 2004: 404) – not least because they also disagree about the distinction between diseases and non-diseases (Smith, 2002; Tikkinen et al., 2012). This indicates a less than clear-cut line between the explained and the unexplained.

So maybe this whole field is a mess and you need to throw out all that psychosomatic stuff and think again?

Standardizing the classification of MUS would therefore require a more thorough reflection over basic concepts such as disease, objective evidence and medical explanation. The potential advantage of doing so would be the ability to determine the value of MUS as a medical category – to test whether it is sensible and helpful to group patients based primarily on their lack of fit with the biomedical paradigm.