PON1 Status in Relation to Gulf War Illness: Evidence of Gene–Exposure Interactions from a Multisite Case–Control Study of 1990–1991 Gulf War Veterans

Steele, Lea; Furlong, Clement E.; Richter, Rebecca J.; Marsillach, Judit; Janulewicz, Patricia A.; Krengel, Maxine H.; Klimas, Nancy G.; Sullivan, Kimberly; Chao, Linda L.

BACKGROUND

Deployment-related neurotoxicant exposures are implicated in the etiology of Gulf War illness (GWI), the multisymptom condition associated with military service in the 1990–1991 Gulf War (GW). A Q/R polymorphism at position 192 of the paraoxonase (PON)-1 enzyme produce PON1192 variants with different capacities for neutralizing specific chemicals, including certain acetylcholinesterase inhibitors.

METHODS

We evaluated PON1192 status and GW exposures in 295 GWI cases and 103 GW veteran controls. Multivariable logistic regression determined independent associations of GWI with GW exposures overall and in PON1192 subgroups. Exact logistic regression explored effects of exposure combinations in PON1192 subgroups.

RESULTS

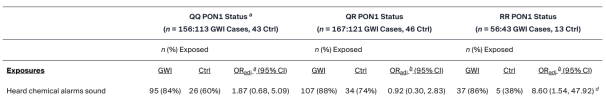

Hearing chemical alarms (proxy for possible nerve agent exposure) was associated with GWI only among RR status veterans (OR = 8.60, p = 0.014). Deployment-related skin pesticide use was associated with GWI only among QQ (OR = 3.30, p = 0.010) and QR (OR = 4.22, p < 0.001) status veterans. Exploratory assessments indicated that chemical alarms were associated with GWI in the subgroup of RR status veterans who took pyridostigmine bromide (PB) (exact OR = 19.02, p = 0.009) but not RR veterans who did not take PB (exact OR = 0.97, p = 1.00). Similarly, skin pesticide use was associated with GWI among QQ status veterans who took PB (exact OR = 6.34, p = 0.001) but not QQ veterans who did not take PB (exact OR = 0.59, p = 0.782).

CONCLUSIONS

Study results suggest a complex pattern of PON1192 exposures and exposure–exposure interactions in the development of GWI.

Link | PDF (International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health) [Open Access]

Steele, Lea; Furlong, Clement E.; Richter, Rebecca J.; Marsillach, Judit; Janulewicz, Patricia A.; Krengel, Maxine H.; Klimas, Nancy G.; Sullivan, Kimberly; Chao, Linda L.

BACKGROUND

Deployment-related neurotoxicant exposures are implicated in the etiology of Gulf War illness (GWI), the multisymptom condition associated with military service in the 1990–1991 Gulf War (GW). A Q/R polymorphism at position 192 of the paraoxonase (PON)-1 enzyme produce PON1192 variants with different capacities for neutralizing specific chemicals, including certain acetylcholinesterase inhibitors.

METHODS

We evaluated PON1192 status and GW exposures in 295 GWI cases and 103 GW veteran controls. Multivariable logistic regression determined independent associations of GWI with GW exposures overall and in PON1192 subgroups. Exact logistic regression explored effects of exposure combinations in PON1192 subgroups.

RESULTS

Hearing chemical alarms (proxy for possible nerve agent exposure) was associated with GWI only among RR status veterans (OR = 8.60, p = 0.014). Deployment-related skin pesticide use was associated with GWI only among QQ (OR = 3.30, p = 0.010) and QR (OR = 4.22, p < 0.001) status veterans. Exploratory assessments indicated that chemical alarms were associated with GWI in the subgroup of RR status veterans who took pyridostigmine bromide (PB) (exact OR = 19.02, p = 0.009) but not RR veterans who did not take PB (exact OR = 0.97, p = 1.00). Similarly, skin pesticide use was associated with GWI among QQ status veterans who took PB (exact OR = 6.34, p = 0.001) but not QQ veterans who did not take PB (exact OR = 0.59, p = 0.782).

CONCLUSIONS

Study results suggest a complex pattern of PON1192 exposures and exposure–exposure interactions in the development of GWI.

Link | PDF (International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health) [Open Access]