Chandelier

Senior Member (Voting Rights)

ULRIKE BINGEL, VISHVARANI WANIGASEKERA, KATJA WIECH, ROISIN NI MHUIRCHEARTAIGH, MICHAEL C. LEE, MARKUS PLONER, AND IRENE TRACEY

Abstract

Evidence from behavioral and self-reported data suggests that the patients’ beliefs and expectations can shape both therapeutic and adverse effects of any given drug.We investigated how divergent expectancies alter the analgesic efficacy of a potent opioid in healthy volunteers by using brain imaging.

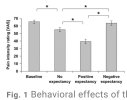

The effect of a fixed concentration of the μ-opioid agonist remifentanil on constant heat pain was assessed under three experimental conditions using a within-subject design: with no expectation of analgesia, with expectancy of a positive analgesic effect, and with negative expectancy of analgesia (that is, expectation of hyperalgesia or exacerbation of pain).

We used functional magnetic resonance imaging to record brain activity to corroborate the effects of expectations on the analgesic efficacy of the opioid and to elucidate the underlying neural mechanisms.

Positive treatment expectancy substantially enhanced (doubled) the analgesic benefit of remifentanil. In contrast, negative treatment expectancy abolished remifentanil analgesia.

These subjective effects were substantiated by significant changes in the neural activity in brain regions involved with the coding of pain intensity. The positive expectancy effects were associated with activity in the endogenous pain modulatory system, and the negative expectancy effects with activity in the hippocampus.

On the basis of subjective and objective evidence, we contend that an individual’s expectation of a drug’s effect critically influences its therapeutic efficacy and that regulatory brain mechanisms differ as a function of expectancy.

We propose that it may be necessary to integrate patients’ beliefs and expectations into drug treatment regimes alongside traditional considerations in order to optimize treatment outcomes.

Gloomy Forecasts Prove True

A pessimist walks into a hospital. His grim prediction that doctors will be unable to alleviate his back pain proved correct—after several days of various treatments, his pain persisted. According to new results from Bingel and colleagues, the gloomy outlook this patient brought with him into his pain treatment may have ensured that his prediction was a self-fulfilling prophesy. Using sophisticated brain imaging techniques, the authors show that one’s expectation of the success of a pain treatment can markedly influence its effectiveness.

In this new study, healthy people were exposed to pain-provoking heat and also given the painkilling opioid drug remifentanil. In advance of each instance of drug administration, the authors informed the subjects that the drug would have no effect, that it would diminish the sensation of pain, or that it would make the pain worse. When subjects expected the drug to be effective, they were not disappointed—they experienced twice as much pain relief as they did when they expected to obtain no benefit from the drug (but did, in fact, get some relief). In contrast, when they expected remifentanil to make the heat pain worse they found that their pain was unchanged. But these subjective reports could be influenced by a host of variables. What was actually happening within the brains of these individuals to shift their pain perceptions so dramatically?

With functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), the authors of Bingel et al. examined brain activity during the experiment. Thermal pain itself causes activation of a so-called pain circuit, which encompasses numerous brain regions including the somatosensory cortex, the cingulate cortex, insula, thalamus, and brainstem. Expectation of increased pain was accompanied by more neural activity in the hippocampus, midcingulate cortex, and medial prefrontal cortex—brain areas that mediate mood and anxiety—than was observed in these regions during expectation of analgesia. Conversely, individuals who expected the drug to mitigate their pain showed increases in the anterior cingulate cortex and the striatum, signs that descending mechanisms of pain inhibition were engaged.

These clues about how our beliefs can affect the way we experience medical treatment for pain can improve the practice of medicine. A drug with a true biological effect may appear to be ineffective to a patient conditioned to expect failure, whether the patient is enrolled in a clinical trial or treated in a physician’s office. Patient education about treatments can help counteract this problem by shaping beliefs to maximize drug effectiveness. If appropriate treatments are accompanied by encouraging words, a pessimist could become an optimist about his future robust health, and thereby make it so.