I had a closer look at this review. It seems that for most outcomes the results were rather conflicting, with the sole exception of natural killer (NK) cell cytotoxicity. Cytotoxicity refers to the ability of NK cells to destroy cancer cells or virus-infected cells. In contrast to other lymphocytes, NK cells can do this without prior sensitization. So researchers can test cytotoxicity by mixing NK cells with some cancer cells and then measuring how many of the cancer cells are destroyed after a certain period of time.

7/11 of studies in the review

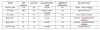

The review by Eaton-Fitch et al. lists 11 studies that have tested NK cell cytotoxicity in ME/CFS. Most (7/11) have reported significant differences between ME/CFS patients and healthy controls. But as the graph below shows, most of these studies (7/11) are also from the same research team, namely the NCNED team from Griffith University that is doing this review. In addition, there are two studies from the Miami team of Mary An Fletcher and Nancy Klimas who have trumpeted this line of research since the end of the 1980s. The two other research teams, one from Spain and a Scandinavian collaboration, did not found a significant difference between ME/CFS patients and controls.

20 Studies not included:

20 Studies not included:

A lot of NK cytotoxicity studies were excluded from this review because (1) the authors required that studies used the Fukuda, Canadian or International Consensus criteria, (2) patients had to be adults and (3) because their literature search ended in March 2018. I think that there are about 20 additional studies that have tested NK cytotoxicity in ME/CFS patients compared to controls, that didn’t make the selection. To be fair to the authors, I don’t think they’ve cherry-picked studies to present the results more favorably as most of the excluded studies also reported significant differences. I’ve made an overview of those additional 20 studies in the graph below (Green = reported significant differences, Red = reported no significant differences).

A bit of history

A bit of history

Four studies are included that did not use an official ME/CFS case definition. I think the

first team that published about reduced NK cell cytotoxicity in this illness was the team of James (aka Jim) Jones in 1985. They were looking at patients who remained ill following Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infection. Back then this was called chronic EBV, but Jones would soon become one the authors of the 1988 case definition for CFS.

Around the same time, towards the end of the 1980s,

a Japanese group reported on a group of patients with unexplained chronic fatigue and a decrease in NK activity. They called it Low Natural Killer Cell Syndrome (LNKS). They had teamed up with

Ronald Herberman, founder of the University of Pittsburgh Cancer Institute and one of the people who helped discover NK cells in the 1970s. That probably sparked some interested in NK cells in researchers looking at patients with unexplained chronic fatigue.

The

Caligiuri et al. study included patients from the outbreak at Lake Tahoe who were seeing Cheney and Peterson. Komaroff was also one of the authors and he would soon become a co-author of the 1988 definition as well. The first study that used that official CFS case definition to report on NK cell cytotoxicity was the

research team of Nancy Klimas from Miami University in 1990. They would go on to publish another three studies on this, including the largest one to date. Multiple research teams have looked at NK cell cytotoxicity in ME/CFS, such as the CDC group of William Reeves (

Mawle et al. 1997). They used patients recruited through their Atlanta surveillance study but couldn’t find significant differences with healthy controls.

How to add up all these results?

So how to make sense of all these results? We can’t do a meta-analysis because most of these studies didn’t report the actual data (and in some cases, we don’t even get a p-value). Simply counting the number of studies that reported a statistically significant difference between ME/CFS patients and controls (as

a 2015 review by Strayer tried to do) probably isn’t accurate either as many of these studies are extremely small. Less than half (15/31) included more than 20 ME/CFS patients. In addition, many of these studies are from the same research team: 8 from the team at Griffith University in Australia and 4 from Klimas/Fletcher team at Miami. So perhaps the best method is to look at the largest studies to see what they have found. I focus on 6 of them, listed below.

By far the largest is the one by

Fletcher et al. published in 2010 in PLOS One. They found a clear difference. The median percentage cytotoxicity (and 25–75th percentile interval) were 28 (20–37) for controls and only 12 (8–21) for ME/CFS patients. They reported an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.77. The second-largest study is the

one reported by the UK Biobank team this year. Because it’s so recent it wasn’t included in the review by Eaton-Fitch. It reported on many other immune abnormalities in ME/CFS (such as MAIT cells) and no exact numbers are given for the NK cells cytotoxicity differences. The authors note that no significant differences could be found for any of the relevant parameters.

Then there’s an

older study that included 91 CFS patients selected with the rather strict Holmes criteria. But I have my doubts about this study. It’s, for example, the only one that didn’t use cancer cells (the K562 cell line) to measure cytotoxicity. Instead, it assessed NK cell activity by “measuring cytolysis of human herpes virus 6 (HHV-6)-infected H9 cells.” The study focuses on how “glyconutrients” can enhance NK cell function in CFS. From what I understand

glyconutrients are just plant sugars. I suspect it’s a fancy term that is often used to try to sell all sorts of supplements. If I Google the first author of this study, Darryl M. See I find that the

Medical Board of California accused him of gross negligence and incompetence, a case that resulted in him losing his medical license in 2007. One of the complaints was that he “failed to conduct a proper work-up of chronic fatigue syndrome so as to rule out other possible causes of the symptoms.” So I have my doubts about this study, although it did report significant differences between patients and controls. Then there are two studies from the Staines/Marshall-Gradisnik team from Griffith University, Australia. There'

s a large one with 95 ME/CFS patients and a

longitudinal one where 65 ME/CFS patients showed consistent lower NK cell cytotoxicity over a 12 month period. Finally, there’s the Swedish/Norwegian collaboration (

Theorelll et al.) that reported no difference between ME/CFS patients and controls (but without giving the data).

Differences in methodology

An interesting question is whether there might be differences in methodology that could explain why some have found a difference while others haven’t. The main question is: how many NK cells do you mix with the cancer cells (the effector to target ratio) and how do you tell the difference between NK Cells, the normal cancer cells and the destroyed cancer cells? The Miami team used an older method involving radioactive material, a chromium 51Cr release assay, to tell the difference and a dilution of 1:1. The Griffith team on the other hand labels cells with a fluorescent dye which allows them to differentiate cells using flow cytometry. They often report using an effector to target ratio of 25:1. Despite these differences, both methods have found significant reduced NK cytotoxicity in ME/CFS samples. That makes me skeptical that differences in methodology are behind the inconsistency and null results.

The handling of blood samples, however, might be an interesting issue. This was raised by Theorell et al. who noted that most studies that found abnormalities either used whole blood (like the Miami team) or isolated cells tested quickly after blood draw (like the Griffith’s team). In contrast, they themselves froze the isolated cells for a while and perhaps that’s why they couldn’t find a significant difference. The authors wrote: “Such a discrepancy would therefore suggest that NK cells from ME/CFS patients in general are intrinsically normal but might be responding to an abnormal external milieu, rendering them hypofunctional in whole blood or immediately after isolation.” This was back in 2017 before there was excitement about ‘something in the blood’ in ME/CFS. So that sounds like an interesting hypothesis. If I understand correctly, the biobank study also froze their samples in contrast to for example the longitudinal study at Griffith University where the authors reported that “all analyses and experiments were performed immediately following blood collection.” In their other big study, the Griffith team reports that “blood samples were analysed within 12 hours of collection.” I think that the 1997 CDC study that reported null results also processed (and froze) their blood samples. It would be interesting if someone with more knowledge than me could have a look at this hypothesis that sample processing might explain the conflicting results on NK cell cytotoxicity. An interesting experiment might be to look at NK cells from healthy people that were put in ME/CFS blood and the other way around.

Another, somewhat less exciting hypothesis is that the studies with null results like the biobank study and the Theorell et al. study, corrected their findings for multiple comparisons, while many of the previous studies didn’t. This is a problem because in many studies several effect-to target ratios were used, which makes it easier to find a significant one (and in some cases not all of these ratios were reported).

This issue was raised by Graham Taylor, an expert on NK cell function and one of the reviewers of the systematic review by Eaton-Fitch et al.

What does it mean?

Overall it seems that the current evidence suggests NK cell cytotoxicity is reduced in ME/CFS, although there is some inconsistency in the findings. Now, what does that mean?

A first thing that is important to highlight is that reduced NK cell cytotoxicity has been reported in several illnesses, not only AIDS or cancer but for example depression as well. It isn’t very specific.

The 2015 institute of Medicine report noted:

“Low NK cytotoxicity is not specific to ME/CFS. It is also reported to be present in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, cancer, and endometriosis (Meeus et al., 2009; Oosterlynck et al., 1991; Richter et al., 2010). It is present as well in healthy individuals who are older, smokers, psychologically stressed, depressed, physically deconditioned, or sleep deprived (Fondell et al., 2011; Whiteside and Friberg, 1998; Zeidel et al., 2002).”

That last part is important. If psychological stress, depression or deconditioning can cause reduced NK cytotoxicity (would need to go through that literature to see if that’s really true), it might be that it’s not so much an expression of ME/CFS but merely one of the downstream effects of being severely ill.

A study by the Miami group suggested that ME/CFS patients with low NK cytotoxicity have more severe symptoms (including worse scores on cognitive tests) than ME/CFS patients with normal NK cytotoxicity. Some other studies have reported this as well, although the data isn’t overwhelming (the larger studies haven’t reported on this, although it seems quite easy to do).

One final explanation is that reduced NK cytotoxicity is not so much a consequence of the disease but a precipitating factor. In other words; people with low NK cytotoxicity could have a higher risk of developing ME/CFS. One of the great mysteries of ME/CFS research is why some people don’t recover from infections such as Epstein Barr Virus while most people do. Low NK cytotoxicity might be one piece of the puzzle. Because NK cells don’t need to be primed with virus-infected cells to get into action, they form the first line of defense. If that first defense is weakened, perhaps the virus can do something in the body that impairs recovery. That’s just speculation though; we would need to test NK cytotoxicity before people get ME/CFS, to see if the theory has any merit.

During the

CDC conference call on September 16, Dr. Unger said that “the results of the NK cell function testing on a sub-set of MCAM participants will be ready for analysis by the end of the year.” MCAM refers to the long-awaited “Standards for the Multi-Site Clinical Assessment of ME/CFS” study. It would be interesting to see what comes out of that.