Jonathan Edwards

Senior Member (Voting Rights)

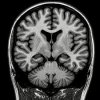

My reading was that amyloid was used as a sort of proxy for general "waste" clearance because advanced tracers have been developed for that molecule.

Thanks for the comments.

I think amyloid is investigated because there has been a theory that amyloid accumulation causes Alzheimer's. That brings in billions in funding. I am not actually aware of any other 'waste' produce that has been suggested to be bad in the brain. Nobody worried about it much before. And now there is a lot of doubt about amyloid being important as a causal driver. The amyloid animal models may have dementia but if you mess about with any protein you may get that.

much harder to see small differences in more common metabolites.

I don't think this is about 'metabolites' which are small molecules that can cross vascular walls. What are usually called 'waste' metabolites are small molecules that leave the tissue and are further degraded by liver or excreted by kidney as for urate and urea. There aren't that many others because burning organic chemicals mostly produces water, CO2 and urea for the nitrogen.

I am not suggesting the brain can do anything special. Maybe just that microglia (brain macrophages) can pinocytose and degrade proteins like macrophages in any tissue

If it is true that the arterial pulsation drives the surrounding fluid in the direction of flow could that not be enough to create some very small flow through the parenchyma by itself?

It could, but is there really a good basis for saying it is important? Brain arteries are relatively inelastic at their point of entry at the circle of Willis. They may be more elastic at smaller caliber deeper in but It would seem a pretty inefficient way of trying to get water in when the whole brain is already bathed in that water and diffusion under oncotic gradient is available.

I remain uncertain why the astrocytes matter much other than as structural guides for convective flow. Maybe water goes through their aquaporins but maybe it mostly goes between them. on the brain surface. I don't see it mattering much.