Recovery of upper limb muscle function in chronic fatigue syndrome with and without fibromyalgia

Authors

Authors

Ickmans K, Meeus M, De Kooning M, Lambrecht L, Nijs J

Institution

Pain in Motion Research Group, Department of Human Physiology and Physiotherapy, Faculty of Physical Education & Physiotherapy, Vrije Universiteit Brussel, Brussel, Belgium

Background

Chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) patients frequently complain of muscle fatigue and abnormally slow recovery, especially of the upper limb muscles during and after activities of daily living. Furthermore, disease heterogeneity has not yet been studied in relation to recovery of muscle function in CFS. Here, we examine recovery of upper limb muscle function from a fatiguing exercise in CFS patients with (CFS+FM) and without (CFS-only) comorbid fibromyalgia and compare their results with a matched inactive control group.

Design

In this case-control study, 18 CFS-only patients, 30 CFS+FM patients and 30 healthy inactive controls performed a fatiguing upper limb exercise test with subsequent recovery measures.

Results

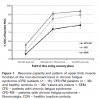

There was no significant difference among the three groups for maximal handgrip strength of the non-dominant hand. A significant worse recovery of upper limb muscle function was found in the CFS+FM, but not in de CFS-only group compared with the controls (P<0.05).

Conclusions

This study reveals, for the first time, delayed recovery of upper limb muscle function in CFS+FM, but not in CFS-only patients. The results underline that CFS is a heterogeneous disorder suggesting that reducing the heterogeneity of the disorder in future research is important to make progress towards a better understanding and uncovering of mechanisms regarding the nature of divers impairments in these patients.

Publication

Eur J Clin Invest 2014 Feb; 44(2): 153–9

Comment by ME Research UK

The fact that muscles take longer to recover after exertion is a characteristic feature of ME, but experimental studies showing this have been few and far between over the past 30 years. In fact, as Dr Kelly Ickmans (ME Research UK research fellow at Vrije Universiteit Brussel) points out in this paper in European Journal of Clinical Investigation, muscle recovery in the upper limb has never been subjected to research in ME/CFS patients, despite the fact that these muscles are most frequently used for everyday activities, such as combing and washing hair, ironing and cooking.

Kelly decided to test muscle function in the upper arm during and after exercise using a simple hand dynamometer which measures force and strength. After an exercise challenge consisting of 18 maximal contractions and a recovery phase of 45 minutes, she found that the muscle recovery was significantly slower in ME/CFS patients than healthy people (muscle strength was still recovering 30-45 minutes after the exercise). Intriguingly, this was only true for patients who also fulfilled the 2010 criteria for fibromyalgia, i.e. who had a high degree of “widespread pain” as well as the symptoms shared with ME/CFS. In fact, it seems that 43–70% of ME/CFS patients also meet the criteria for fibromyalgia, so this test could be a simple, easy-to-perform way of objectively measuring delayed muscle recovery in a substantial number of people.

One take-home message from this investigation is that meaningful experiments don’t have to be complex and expensive, and that even simple ones, like the change in upper arm strength over a short period, can yield useful information. In fact, the results remind us of a study we funded at the University of Dundee in 2004, which showed that a significant number of patients had easily measureable

muscle weakness in the lower limbs and absent or abnormal nerve reflexes.