- Home

- Forums

- ME/CFS and Long Covid news

- ME/CFS and Long Covid news

- Psychosomatic news - ME/CFS and Long Covid

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Swiss Re: Expert Forum on secondary COVID-19 impacts, Feb 2021

- Thread starter Sly Saint

- Start date

Kalliope

Senior Member (Voting Rights)

Sly Saint

Senior Member (Voting Rights)

Video of the presentation posted on another thread

"This is the video of Michael Sharpe's presentation on Long COVID to Swiss Re. It may have been removed from their website now, but, fortunately, it's been uploaded to a file-sharing site, in order that such an extraordinary contribution to medical history can be archived for posterity!"

"This is the video of Michael Sharpe's presentation on Long COVID to Swiss Re. It may have been removed from their website now, but, fortunately, it's been uploaded to a file-sharing site, in order that such an extraordinary contribution to medical history can be archived for posterity!"

Invisible Woman

Senior Member (Voting Rights)

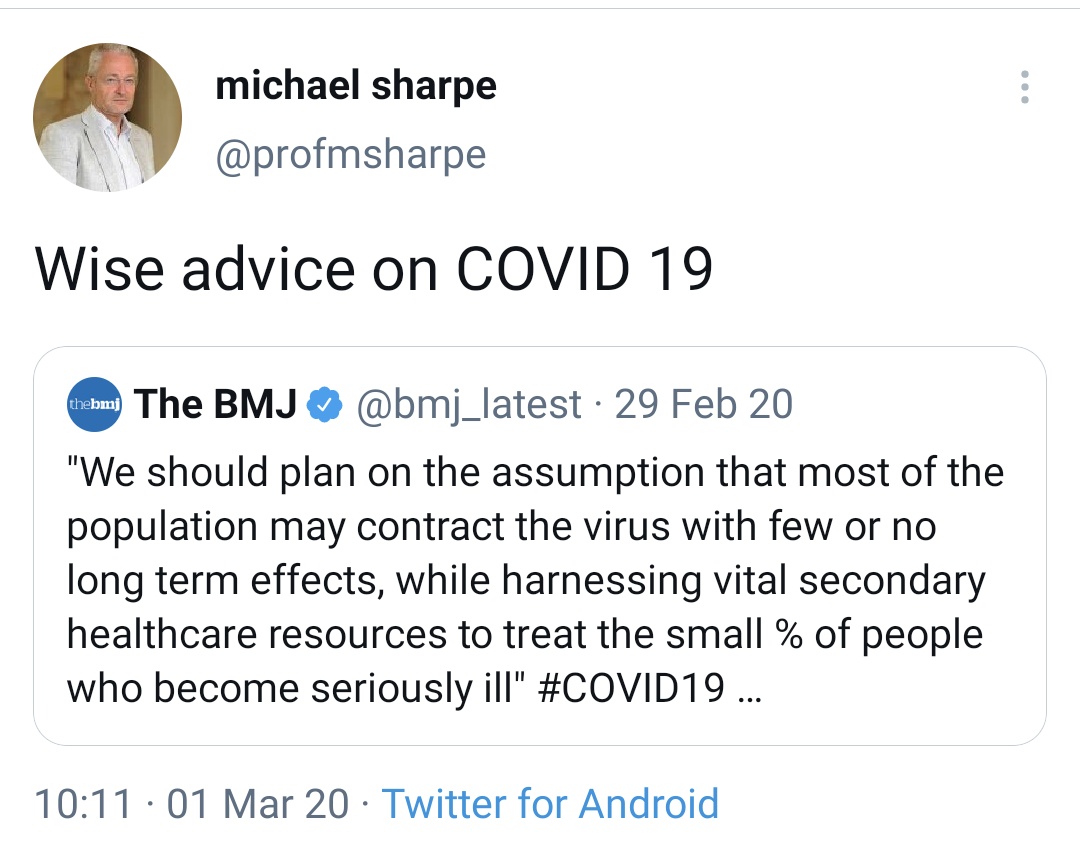

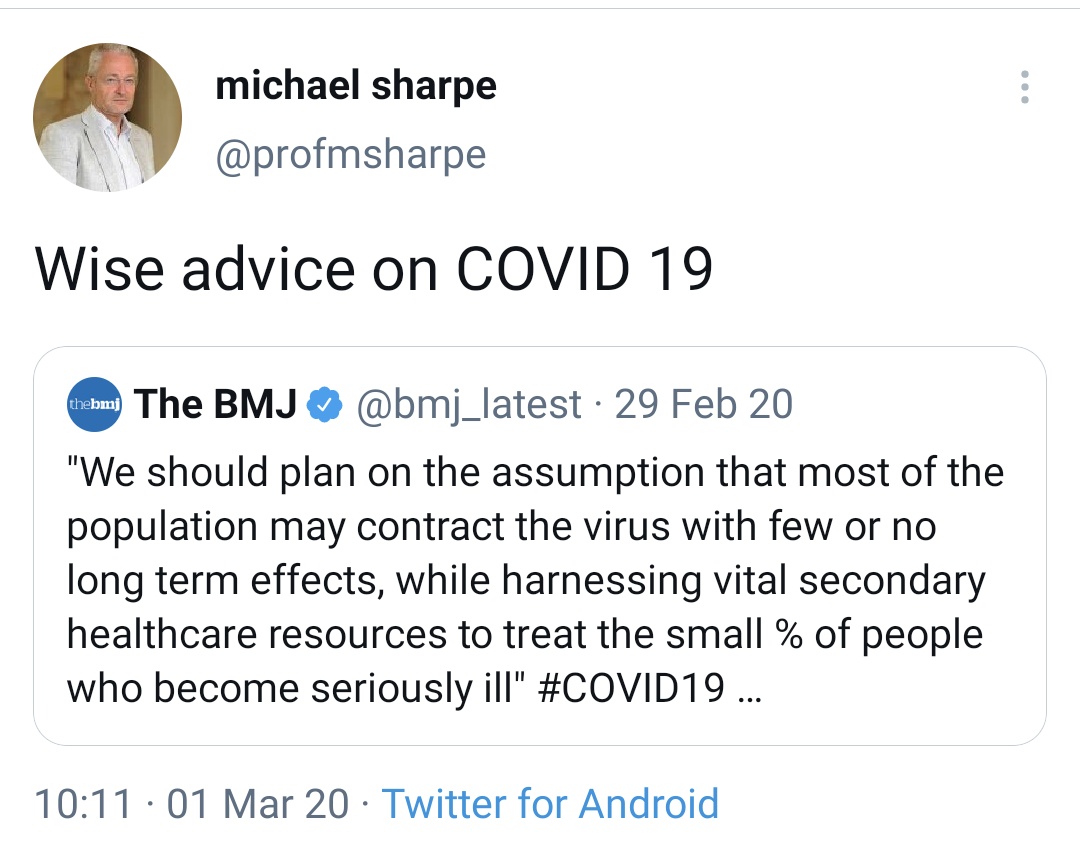

George Monbiot's tweet

I think that's the wrong question. Here are some alternatives -

1. What is it worth to them to carry on denying the suffering of hundreds of thousands of people in the UK & millions worldwide?

2. In these "woke" times how long will the business model of denial of suffering and stigmatizing some of the most vulnerable in society continue?

3. Psychiatrists like Sharpe & Wessely plus other mental health care professionals like Chalder work with many extremely vulnerable people. They have a history stigmatizing the patient and denying their illness. Where is the oversight to stop this continuing?

I wonder whether the people who so airily dismiss Long Covid, ME and CFS as "psychosomatic" or "imaginary" have any idea of how real and horrible is the suffering experienced by so many people with these conditions, or of how desperately they try to recover.

I think that's the wrong question. Here are some alternatives -

1. What is it worth to them to carry on denying the suffering of hundreds of thousands of people in the UK & millions worldwide?

2. In these "woke" times how long will the business model of denial of suffering and stigmatizing some of the most vulnerable in society continue?

3. Psychiatrists like Sharpe & Wessely plus other mental health care professionals like Chalder work with many extremely vulnerable people. They have a history stigmatizing the patient and denying their illness. Where is the oversight to stop this continuing?

Looks like awareness of this is growing in the LC community. Darren is (or part of) Long Covid Physio.

I think they've badly underestimated the difference between gaslighting LongCovid and M.E. patients. Using the same old tired, discredited arguments against a vast group of people who are largely in contact with each other and all got ill at roughly the same time is not going to work this time. It's quite sad and pathetic really.

Wyva

Senior Member (Voting Rights)

This is something I really would like to think. But I'm also kind of worried because in the last few weeks I've seen some long haulers saying things like "it also depends on if you want to get better - because some people just don't", "the mindset matters a lot", "you have to get back to being active, the symptoms will disappear after a while" etc.I think they've badly underestimated the difference between gaslighting LongCovid and M.E. patients. Using the same old tired, discredited arguments against a vast group of people who are largely in contact with each other and all got ill at roughly the same time is not going to work this time. It's quite sad and pathetic really.

Yesterday I saw an article in a popular women's magazine here, where the author used to be a long hauler and he said stuff like: "if you are physically able, you have to get off the couch and push yourself to go out and do things, no matter how week you feel or how little motivation you have". He equated brainfog with a state of lack of motivation and feeling hopeless. These are long haulers or former long haulers and this worries me. I don't know if they just repeat what their doctors told them or they came up with this themselves. (Or if they have the ME/CFS-like long covid and not some other sequelae.)

(I could mention that no one said anything like this in the glandular fever forums I frequented in my first 1-2 years and where almost everyone had post-viral fatigue syndrome, and people with acute cases were really rare, so it was basically a "long mono" group. Everyone was convinced there that the symptoms are real, however that forum was smaller than the LC groups, so it may be due to simple statistics and not something else.)

On the flipside: there are definitely long haulers who are adamant about this not being a psychosomatic issue.

Wonko

Senior Member (Voting Rights)

In a legal case wouldn't they just call an 'expert' witness in their defense? They only have to show that they acted in accord with 'best practice' and as they direct that......If one, or a group of individuals is blamed for causing, generating, supporting, and/or aiding the continuance of a devastating disease, what might the legal ramifications of this be? Hmmmm....

Good point @ Wonko. This would appear to be a likely scenario in a legal situation. Maligning whole groups could be explained as "best practice".

On another note, journalists daren't write about anything of concern, e.g. wars, disease, widespread financial collapse, for fear of being blamed for causing these catastrophes.

On another note, journalists daren't write about anything of concern, e.g. wars, disease, widespread financial collapse, for fear of being blamed for causing these catastrophes.

rvallee

Senior Member (Voting Rights)

One thing I think should be mentioned: this is Sharpe's main career focus, he has spent decades "studying" this, wrote books and academic/clinical chapters, taught it as a professor, was gifted millions to pursue his expertise, publishing dozens of papers, presenting to professional audiences and more.

And this presentation, entirely devoid of substance, relying on a combination of circular logical fallacies, anecdotes and innuendo, is essentially a full summary of the extent of his knowledge on the issue. In presenting the sum of his career's work to a professional audience, likely paid, this is the best he can do.

There is nothing of substance in this presentation. It's entirely vague and contains no expert knowledge whatsoever. And still, it actually represents the actual sum of the knowledge this "expert" has on his main topic of expertise. I'm sure he could ramble on for hours elaborating but there would still be no substance there, only more rhetoric and sophistry.

And this pathetic accumulation of ignorance has ruined millions of lives. It's truly unbelievable when the facts are simply stated.

And this presentation, entirely devoid of substance, relying on a combination of circular logical fallacies, anecdotes and innuendo, is essentially a full summary of the extent of his knowledge on the issue. In presenting the sum of his career's work to a professional audience, likely paid, this is the best he can do.

There is nothing of substance in this presentation. It's entirely vague and contains no expert knowledge whatsoever. And still, it actually represents the actual sum of the knowledge this "expert" has on his main topic of expertise. I'm sure he could ramble on for hours elaborating but there would still be no substance there, only more rhetoric and sophistry.

And this pathetic accumulation of ignorance has ruined millions of lives. It's truly unbelievable when the facts are simply stated.

Invisible Woman

Senior Member (Voting Rights)

Yesterday I saw an article in a popular women's magazine here, where the author used to be a long hauler and he said stuff like: "if you are physically able, you have to get off the couch and push yourself to go out and do things, no matter how week you feel or how little motivation you have". He equated brainfog with a state of lack of motivation and feeling hopeless. These are long haulers or former long haulers and this worries me. I don't know if they just repeat what their doctors told them or they came up with this themselves. (Or if they have the ME/CFS-like long covid and not some other sequelae.)

Ah but there's a big difference between someone who can get up and get their behind off the sofa, even if it feels very difficult and they're tired and not in the mood, and someone who can only do this once, twice or not at all.

I've experienced bouts of illness that have left me too weak to stand long before I got ME. As a youngster I was up and running about in no time.

As an adult, even a young adult it is harder because you have other commitments - exams, work etc. So it may take longer and regaining fitness does take effort and motivation.

That is not the same thing at all as having ME. I daresay for many with long covid it won't be the same thing either. If you are able to get off that couch and slowly regain your stamina and health then by definition you do not have the same thing. It really is that simple.

Comparing yourself to someone suffering from ME or long covid that is ME-like is like an Olympian athlete wondering why you, as a healthy person, can't compete with them as a chosen sport.

It's a nonsense.

One thing I think should be mentioned: this is Sharpe's main career focus, he has spent decades "studying" this, wrote books and academic/clinical chapters, taught it as a professor, was gifted millions to pursue his expertise, publishing dozens of papers, presenting to professional audiences and more.

And this presentation, entirely devoid of substance, relying on a combination of circular logical fallacies, anecdotes and innuendo, is essentially a full summary of the extent of his knowledge on the issue. In presenting the sum of his career's work to a professional audience, likely paid, this is the best he can do.

There is nothing of substance in this presentation. It's entirely vague and contains no expert knowledge whatsoever. And still, it actually represents the actual sum of the knowledge this "expert" has on his main topic of expertise. I'm sure he could ramble on for hours elaborating but there would still be no substance there, only more rhetoric and sophistry.

And this pathetic accumulation of ignorance has ruined millions of lives. It's truly unbelievable when the facts are simply stated.

Bravo!

rvallee

Senior Member (Voting Rights)

Turns out it's actually worse than this, a "world-leading expert" on the topic of post-infectious illness literally did not see the obvious coming, the obvious that much of the patient community did predict and warn about, as well as the actual experts that this ignoramus dismisses.

Turns out that fake expertise is indeed entirely fake and of no value whatsoever in itself. In this case Sharpe is doing exactly the only value his quackery has ever had: provide insurers with implausible cover the same way the scientists working with the tobacco industry to kill people for profit did.

Turns out that fake expertise is indeed entirely fake and of no value whatsoever in itself. In this case Sharpe is doing exactly the only value his quackery has ever had: provide insurers with implausible cover the same way the scientists working with the tobacco industry to kill people for profit did.

I don't have any medical training; perhaps others with expertise in the area of lung disease etc., may wish to comment.

Did I hear correctly on the presentation:

Fibrosis from COVID is reversible?

This article doesn't seem to paint such a definite picture:

Indian J Tuberc. 2020 Nov 10

doi: 10.1016/j.ijtb.2020.11.003 [Epub ahead of print]

PMCID: PMC7654356

Post covid 19 pulmonary fibrosis- Is it reversible?

Deependra Kumar Rai,∗ Priya Sharma, and Rahul Kumar

Author information Article notes Copyright and License information Disclaimer

Go to:

Abstract

After the COVID-19 outbreak, increasing number of patients worldwide who have survived COVID-19 continue to battle the symptoms of the illness, long after they have been clinically tested negative for the disease. As we battle through this pandemic, the challenging part is to manage COVID-19 sequelae which may vary from fatigue and body aches to lung fibrosis. This review addresses underlying mechanism, risk factors, course of disease and treatment option for post covid pulmonary fibrosis. Elderly patient who require ICU care and mechanical ventilation are at the highest risk to develop lung fibrosis. Currently, no fully proven options are available for the treatment of post inflammatory COVID 19 pulmonary fibrosis.

3. Conclusion

Considering huge numbers of individuals affected by COVID-19, even rare complications like post covid pulmonary fibrosis will have major health effects at the population level. Elderly patient who require ICU care and mechanical ventilation are the highest risk to develop lung fibrosis. Currently, no fully proven options are available for the treatment of post inflammatory COVID 19 pulmonary fibrosis.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7654356/

ETA: Thank you @Esther12 for the transcript of this talk.

From the transcript re fibrosis:

"the main imaging abnormalities are just

um chest x-ray and chest ct

where you generally see resolving

fibrosis and that's

that's the main abnormalities that we see"

ETA #2:

From this same study -

"Many studies have shown that most common abnormality of lung function in discharged survivors with COVID-19 is impairment of diffusion capacity, followed by restrictive ventilatory defects, both associated with the severity of the disease21 , 22 Both decreased alveolar volume and K CO contribute to the pathogenesis of impaired diffusion capacity.23 At 3-months after discharge, residual abnormalities of pulmonary function were observed in 25.45% of the cohort which was lower than the abnormal pulmonary function in COVID-19 patients when discharged.10 Lung function abnormalities were detected in 14 out of 55 patients and the measurement of D-dimer levels at admission may be useful in prediction of impaired diffusion defect.16"

Did I hear correctly on the presentation:

Fibrosis from COVID is reversible?

This article doesn't seem to paint such a definite picture:

Indian J Tuberc. 2020 Nov 10

doi: 10.1016/j.ijtb.2020.11.003 [Epub ahead of print]

PMCID: PMC7654356

Post covid 19 pulmonary fibrosis- Is it reversible?

Deependra Kumar Rai,∗ Priya Sharma, and Rahul Kumar

Author information Article notes Copyright and License information Disclaimer

Go to:

Abstract

After the COVID-19 outbreak, increasing number of patients worldwide who have survived COVID-19 continue to battle the symptoms of the illness, long after they have been clinically tested negative for the disease. As we battle through this pandemic, the challenging part is to manage COVID-19 sequelae which may vary from fatigue and body aches to lung fibrosis. This review addresses underlying mechanism, risk factors, course of disease and treatment option for post covid pulmonary fibrosis. Elderly patient who require ICU care and mechanical ventilation are at the highest risk to develop lung fibrosis. Currently, no fully proven options are available for the treatment of post inflammatory COVID 19 pulmonary fibrosis.

3. Conclusion

Considering huge numbers of individuals affected by COVID-19, even rare complications like post covid pulmonary fibrosis will have major health effects at the population level. Elderly patient who require ICU care and mechanical ventilation are the highest risk to develop lung fibrosis. Currently, no fully proven options are available for the treatment of post inflammatory COVID 19 pulmonary fibrosis.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7654356/

ETA: Thank you @Esther12 for the transcript of this talk.

From the transcript re fibrosis:

"the main imaging abnormalities are just

um chest x-ray and chest ct

where you generally see resolving

fibrosis and that's

that's the main abnormalities that we see"

ETA #2:

From this same study -

"Many studies have shown that most common abnormality of lung function in discharged survivors with COVID-19 is impairment of diffusion capacity, followed by restrictive ventilatory defects, both associated with the severity of the disease21 , 22 Both decreased alveolar volume and K CO contribute to the pathogenesis of impaired diffusion capacity.23 At 3-months after discharge, residual abnormalities of pulmonary function were observed in 25.45% of the cohort which was lower than the abnormal pulmonary function in COVID-19 patients when discharged.10 Lung function abnormalities were detected in 14 out of 55 patients and the measurement of D-dimer levels at admission may be useful in prediction of impaired diffusion defect.16"

Last edited:

Esther12

Senior Member (Voting Rights)

Video of the presentation posted on another thread

"This is the video of Michael Sharpe's presentation on Long COVID to Swiss Re. It may have been removed from their website now, but, fortunately, it's been uploaded to a file-sharing site, in order that such an extraordinary contribution to medical history can be archived for posterity!"

Auto-transcript part 1:

Transcript

so it's my great pleasure um to

introduce professor michael sharp

and i'll let him take over the screen

and share his slide deck but i'll tell

you a little bit about him

he's a professor of psychological

medicine at the university

at oxford university hospital um also

president of the academy of consultation

liaison psychiatry in the us

and vice president of the european

association of psychosomatic medicine

so that's a great cv and background to

talk to us today about postcovid

thank you thank you very much

um can you see my slides

we can thank you good excellent right

thank you so much

for inviting me um i i think maybe i'm

here for

a couple of main reasons

[Music]

one of them which is i've had a

career-long interest

in fatigue and the treatment of fatigue

but the other one is that i helped to

set up

our post covid clinic in oxford

which is based in the respiratory

department but which is

multidisciplinary and so i've i've had

some clinical experience of the kind of

patients that we're seeing

which i'm going to share with you um

given i'm giving the first talk in the

meeting i think it

might be important that we um at least

try and

agree what we're talking about uh not

entirely straightforward

um nice in the uk um

has offered us some definitions and as

you'll see

uh there's acute ongoing but it's

postcoded 19 at the bottom

that we're concerned about here

and this is setting a time of

12 weeks it doesn't specify any kind of

severity it just says signs and symptoms

and it does say not explained by another

diagnosis so this may not be universally

accepted

but we're working on people who have

significant symptoms

three months after an apparent infection

although those are not always documented

now i already heard this mentioned i'm

going to

intersperse my talk with some take away

messages

and one of them is it's been a tough

time for academics i can say as one

they've been stuck in their bedrooms

so what have they done they've done a

lot of internet surveys

and and that can give us some clues but

it's absolutely hopeless

uh giving us any kind of prevalence

estimates

and so uh because we never quite know

who denominator is it's just the people

that clicked on the questionnaire

so please be aware of this deluge of

poor quality research with unclear

denominators

there is some better research as you

heard coming down the track

so we all know about acute covid who

gets

so-called long-covid or becomes a long

hauler or post covered syndrome

everything i say is based on what's

published uh interpreted through

clinical and clinical uh experience

none of these are solid facts because

this is an evolving

evolving area of understanding but we're

probably thinking of five to ten percent

of patients at three months have some

kind of

severity of symptoms and disability many

more may

have lesser symptoms and lesser

disability they tend to be older

predominance of females and pre-morbid

vulnerability

asthma possibly depression

in oxford as in many other uk centers

we've set up a multidisciplinary clinic

um and this seas started off seeing

people had been admitted to hospital but

under pressure from primary care

it now sees in fact the majority of

patients are referrals from primary care

as you can see consistent with the nice

recommendation it has a range of

disciplines

in a one-stop shop multi-disciplinary

clinic

and we also have a virtual

multi-disciplinary team where we can

bring in cardiology neurology and so on

when needed

this has been a very interesting

development i think this is how medicine

should be practiced

but of course it's on short-term funding

um and long-term funding is promised but

who knows so let's start with a case

um there's a range of types of people

and symptoms but if it was to be a

common case

that would be a gp referral and most of

the

the more curiously the more complex

patients tend to be the gp referrals not

the hospital discharges

a woman in her 30s 40 uh

teacher small children had a coveted

like illness about six months ago

wasn't tested so we have to take it on

the symptoms

and is now presenting to the clinic with

disabling fatigue

that she says is made worse when she

does things widespread aches and pains

short of breath and feeling of heaviness

in the chest

and generally very anxious about her

illness and about what's going to happen

and has not been back to work since the

um since she became ill so there's a

wide range of presentations but this

would be a common type of presentation

and as you'll see the symptoms that she

presents are the same as the ones

that come out in surveys so chest pain

shortness of breath

sometimes cough aches and pains and the

most common

and often most disabling symptom fatigue

the other thing you'll notice from this

diagram is there are a lot of symptoms

and i should say that's a short list

compared to some of the things you'll

see if you look on the web

so we're dealing with a large number of

symptoms with certain ones

core to this presentation i think

importantly for our talk today

it's not just symptoms it's function and

particularly

work uh this is data just from a hundred

patients

seen in the postcode clinics in oxford

and cardiff

and as you'll see more than half are not

back at full time work

six months after infection and a quarter

have not gone back to work at all

um this is mainly hospitalized patients

so in the non-hospitalized patients the

figures may even be higher

so so that's the that's the the

presentation

that we're dealing with what do we know

about the causes

and my takeaway message for causes is

that

it's very easy to find oneself talking

about postcovid syndrome as if it's a

thing like lung cancer

and i don't think it's just the

presentations so we must allow for the

fact that it'll be heterogeneous

and we must be very wary about thinking

about a single cause

and in fact the clinical experiences the

causation

is complex so i'm just going to run

through

potential causal factors um

on the basis of our clinical experience

um

as biological psychological and social

so the thing that everyone thinks about

is organ damage

and clearly there is frequently some

damage to lungs

our experience is that tends not to

progress and usually tends to resolve

people do have acute abnormalities in

kidneys heart

possibly brain um but again what we're

finding is to follow up

the relevance of these abnormalities to

people's presentation

is often unclear and often there isn't

very much in the way of investigation

abnormalities

people hypothesize that some resetting

of immune function

that remains a hypothesis it's not

apparent on normal testing

patients often complain of tachycardia

or postural blood pressure drops

and that's um referred to as autonomic

dysfunction i don't think anyone really

understands that

i think it's largely assumed to be

something that will be reversible but

it's a physiological abnormality

and then of course um this is often been

a serious illness

and as the consequence is the way people

have coped with it so if they've gone

from being

running marathons to lying in bed that's

going to have profound effects on their

physiology and their muscle mass

some people become very preoccupied with

their breathing very anxious with their

breathing

maybe over breathe and that of course

can produce

biochemical changes and make people feel

unwell

so there are a range of biological

factors

and the the specific evidence of organ

damage

is present in some people but it is not

the majority

at least not the majority is the cause

of the symptoms

and one of the things i see written a

lot i wanted to

take away message is these people have a

lot of symptoms often

may have 20 30 symptoms multi-symptom

illness does not mean multi-system

pathologies people talk about systems

related to the

heart the lung the brain and that

doesn't mean that those organs are all

diseased it just means the patient

has multiple symptoms

so let's move on to the psychological

factors and what's very striking in some

of our patients

is what you might call health anxiety

they're very focused on bodily symptoms

uh they're worried understandably what

they might mean

particularly focused on breathing and

experience of being breathless

anxiety is prevalent in this population

a third to a half of patients have

significant anxiety

and because of that fearfulness they may

avoid going out and they may spend a lot

of time seeking information

about their condition because it's known

to be a little mysterious

and they may seek a lot of medical care

and we'll come back to that

i think i my colleagues think that

social factors

have an influence in shaping these

presentations and the concern about

symptoms

so here's an article by a well-known

journalist in a well-known newspaper

and as you can see he says that uh

long cove could mean lifelong coping the

effects can be horrible

there's damage in the lung heart and

brain and we should all fear lasting

consequences

so if you're a somewhat vulnerable

disposition and you're feeling unwell

and you don't know much about your

illness that is likely to make you more

concerned

and is not conducive to a positive

approach to recovery and inevitably as a

feature of the modern world

there are a lot of online groups being

even more important in this pandemic

um great benefit to many patients who

feel worried about their symptoms and

feel maybe they're the only one to be

able to share those experiences and get

some support

potentially downside as we've seen with

the chronic fatigue and me groups

who are also moving into this space to

some degree is the people that recover

tend to leave

and you end up over time with the poor

prognosis people

who have a rather pessimistic view of

the illness that they transfer to other

people

so i'm not sure that all the support

groups have been entirely helpful

in encouraging the patient to take a

positive approach

and of course our old friends doctors

are sometimes unhelpful here this is a

quotation from an immunologist

that was reported in nature um

their physicians don't believe them and

so they get psych referrals

so you know it's not really real you're

sent to psychiatry

and his mission is to tell the people i

have a real disease

and what's causing it and of course

that's an another

noble mission but it can lead to

excessive investigation

often an investigation in multiple

species over a period of time

which isn't necessarily helpful to the

patient

and indeed can entrench the patient in

worries

that they have a disease and again

distract them from the task

of rehabilitation so

we don't know the causes so please uh

accept that what i've said is based on

uh clinical experience and a smattering

of evidence

but we think probably certainly for the

primary care patients

by a psychosocial perspective these

different factors

interplaying in different ways is gets

more and more relevant as the patient's

illness and disability

gets more chronic

so we're dealing with a heterogeneous

and complex syndrome what do we know

about

treatment and and here another takeaway

message

in working in the clinic is some of my

colleagues feel that they need to keep a

completely open mind on this condition

it's a new illness

anything could be going on so they need

to do as many tests as possible

whereas the opposing approach is

actually

we don't know but most of this looks

pretty familiar this is anxiety it's

chronic fatigue

we know how to treat those we know about

rehabilitation let's just be pragmatic

and i think one of the real challenges

for managing this condition is

somehow to keep that balance and not to

go too far and over investigation and

not to get too complacent that we know

what's going on

it's a challenge

Esther12

Senior Member (Voting Rights)

part 2:

so the basic management

that

we would do in the clinic and this is

good

management for anything really is that

the patients often come to the clinic as

they do with these kinds of illness

feeling uh not believed feeling that

maybe people are accusing them of making

up their symptoms no one's really taken

an interest

and so spending some time listening to

and showing you uh believe their

experience is really

first base and if you don't do that you

it's hard to get much further to be

honest so that's a crucial starting

point

i think the physicians have to manage

the patient's uncertainty and their own

uncertainty

in deciding how many avenues to go down

with possibilities and tests

and how much to be pragmatic

we must remember it's heterogeneous and

we do find treatable conditions

um about 10 percent have major

depression

uh a significant number have new onset

or exacerbation of asthma

we occasionally find hypothyroidism so

there are simple

things to treat that one can find and

treat

i think what's really important is that

as far as we know most people improve

and so

to give an overall positive message

rather than this is a very worrying

alarming condition that we don't

understand and we don't know what's

going to happen to you

and then the approach for most people is

a

gentle slow return to activity

and at this point some of you uh will be

noticing there are some similarities

here with

approaches to many other illnesses

chronic fatigue syndrome

post line post head minor head injury

all these things

um and indeed there are and it's

tempting to see

kovid as chronic fatigue syndrome with a

cough

but i think that's a little bit

dangerous to make just facile

comparisons but there certainly are some

similarities

and so we don't have any randomized

trials of treatment and postcoded yet

because we haven't had time to have them

done but we have got randomized

trials in these related conditions so

this is the trial

that uh i did with colleagues about 10

years ago

in chronic fatigue syndrome and

basically different treatments were

tested you can see here smc

standard medical care gets graded

exercise

apt is pacing living within your limits

and cbt

cbt so basically they fall into the

the rehabilitative treatments those that

encourage

people with care to gradually build on

what they can do and not worry too much

about the consequences of that

that's the bottom two and the top two

are the ones the more conservative ones

just medical care

or live within your limits and you could

see there at 52 weeks in this

trial there was a clear greater

reduction in fatigue

perhaps paradoxically of those that had

the more active rehabilitation

and similar greater physical

function in those that had the more

active rehabilitation

and this idea of just pacing just

accepting your limits

is no better and possibly actually

slightly worse than nothing

than medical care so that has been

again some you may know immensely

controversial

because uh some of the patient groups

are very against this they feel it's um

it's harmful it's uh not validating

their illness

and so that leads to some potential

difficulties

for us in helping patients but i think

at the moment

if you've found and treated the obvious

things you can treat

the best approach to pros covid is

accepting it'll take time

and doing what i might call

psychologically informed robot

rehabilitation explicitly dealing with

worries

but helping them very gently return to

activity

so if rehabilitation is at the moment

our best hope what are the challenges in

providing that to our patients

well the obvious challenge is there

aren't many rehabilitation

multi-disciplinary teams as you could

see a picture of there

they're being set up certainly in some

places in the uk

with short-term funding um as we have in

oxford but

it's patchy the national health service

in the uk

isn't generally good it's good as acute

illness it's not quite so good at

rehabilitation

and the complicating factor is that nice

who is the authority that

that recommends treatments is

potentially in a contrary position

they've done provisional guidelines on

the management of post covid

which are good guidelines uh i think

that they're they're not very specific

but they're very sound

but they're also doing guidelines on

any chronic fatigue syndrome which in

their current form

they're being revised in in the light of

feedback

are say you shouldn't have

rehabilitation and graded exercise

so i don't know how that's going to play

out but that may complicate the

provision of treatment

for postcovid patients

so what you really want to know is

okay there's all this stuff it's very

complicated and we rehabilitate

how well are people going to do how many

going to end up

from the swiss re perspective of having

chronic disability and chronic work

disability

and that's the one thing of course we

don't know because it hasn't been around

long enough

but i think our experiences to date

that most patients do do improve um

it may be slow we may be talking months

rather than weeks

but with some advice a bit of follow-up

most people do improve

so as far as we can see that approach of

getting people to have a sound

understanding

and not worry too much and work on

rehabilitation is helpful

in the absence of really good data um

physicians usually fall back as you know

on the rule of thirds

so my guess would be about a third these

people won't do so well

about a third will do very well and

about a third will be somewhere between

the two

and so if we say we've got five percent

and we

applies the rule of thirds a guess would

be

someone something like one percent of

these people may have some long-term

disability

uh that is a guess and it'll depend on

the care people get

but given the number of people with

covid that could potentially be quite a

lot of people

sorry nice slides there we go so i want

to provide another case study this is an

unusual case study because um

this one is in the public domain this is

paul garner who's a professor of

medicine

university of liverpool and he's

actually

blogged in the bmj uh

his initial onset

of long covered and now his recovery

and it it's probably worth reading so he

had a

kobe like illness he was very

symptomatic and disabled he couldn't

work

he describes it very well and then he

actually

he was becoming to believe he had me a

chronic possibly lifelong illness and

then he had contact with someone

expert in rehabilitation of chronic

fatigue syndrome and he recovered

quite quickly with a different approach

of rehabilitation

so we don't want to argue too far from

single cases

but it's such a high profile example

it's quite interesting and one you can

read about

oops so um

apologies for that so just to summarize

um those are my take-home messages

beware of the poor quality research

don't assume post-covet is a thing just

because they've got a lot of symptoms

doesn't necessarily mean there's a lot

wrong with them

um we need this open mind of balancing

it could be all sorts of things with we

need to be pragmatic

there are similarities with other

illnesses like chronic fatigue syndrome

probably the best treatment is

psychologically informed rehabilitation

at the moment that may change and

from the insurers point of view i

suspect there is likely to be long-term

disability

and the precise numbers and severity i'm

afraid remains to be seen

those are three things that are probably

worth looking at the nice guidance

um there's a very recent sensible paper

from a respiratory clinic by

sykes in lung and paul garner's essays

in the bmj for a patient perspective

thank you very much

thank you professor sharp that's

incredibly helpful

we have lots of questions as you uh you

might imagine

um so i'll start going through some of

those one question

i had actually was whether you noticed

any marked differences in the kind of

patients that you saw that rooted from

being followed up after discharge from

admissions with covid

versus the referrals that you had from

the community

um yes that may change over time

um but quite a striking difference

the patients will be in hospital tend to

be

older and even even elderly at their

follow-up

three months um they often have some

respiratory symptoms

they may have had some deconditioning

they're being in itu

but they're relatively simple that's

what they've got

the ones we're getting from primary care

these are averages on average and much

more complicated with much more anxiety

depression complex backgrounds mixed in

so that may just be an artifact of

current referral patterns

and it may be the ones that seem most

complex the gps are referring

and we'll see how it evolves over time

but it has been a striking

observation in the clinic yes

interesting um

another question we had was around um

determining the veracity of reported

symptoms

so you have this issue of of belief

having an impact on on prognosis

versus kind of whether any there's any

manipulation of

of symptoms what's your experience of

that

well that's a complex area isn't it and

it applies to all of medicine

i think one's more likely to see that

whether whatever the illness if people

stand to gain or lose

on an insurance policy or whatever

leaving the army or whatever

i think at this stage in the game at the

relatively early stage

i think people's if there is an excess

symptom presentation

it's driven more by fear and anxiety by

and possibly attempt possibly to

convince the doctors but mainly by fear

and anxiety

rather than any attempt to manipulate i

think as any illness as you know any

illness gets chronic

and people stand to gain a large payout

whatever then people

may obviously emphasize their symptoms

we're not seeing that at the moment

and thank you and another question um

from the floor is is regarding um the

impact of the

long covered clinic work on

re-hospitalization

do you have any feel for whether it's

managed to reduce that or whether

whether it's a separate issue

um well in in oxford thankfully we

we didn't have a massive we had a

moderate number we didn't have a massive

number of hospitalized cases

uh and the majority of people now been

seen in our clinic uh primary care

referrals it's hard to know

one of the things we have found that

we're trying to do with the

clinic is prevent the multiple referrals

so when i was saying

that people get referred to multiple

specialties that isn't just within the

clinic

people are rattling around the hospital

as you can imagine from cardiology to

neurology to rheumatology

and i think one benefit of having a post

kobe clinic is you can try and pull them

in

and keep a handle on that and so you

know we have a cardiologist we'll

join virtually in our mdt but the

patients don't all have to go to

cardiology

so i think we are containing the

healthcare use and hopefully the adverse

effects of all those opinions on the

patient

excellent thank you um one question um

was regarding whether there are any

imaging studies that might link to

factors in in the the fatigue elements

of of long covered or wider are you

aware of any

any imaging studies on that topic do you

know if we

go into the literature on chronic

fatigue syndrome and other fatigue

states there are thousands

of studies of all sorts of things and

there certainly are imaging studies um

i don't i'm not aware of anything that's

giving us a generally accepted answer in

either condition

but whatever your hypothesis you will

find a a study

and some of those may turn out to be

right but at the moment but they're not

accepted the main

the main imaging abnormalities are just

um chest x-ray and chest ct

where you generally see resolving

fibrosis and that's

that's the main abnormalities that we

see

one last question before we move on to

our next speaker is um

regarding the the change in the the nice

guidelines um and i'm wondering whether

that has any impact on

our ability to to manage this this

patient group

gosh well that's an interesting uh

highly political

moving uh target there um

the nice guidance existing nice gardens

for chronic fatigue syndrome

me advocated rehabilitation in the form

of cbt graduate exercise

the revision of the guidance which has

been very driven by

by patient groups who feel strongly

about this

is going was going to be very different

that's been out to consultation

i know several royal colleges have

pushed back very hard indeed on that

and it's being considered and that will

come out in march

on the positive side at the moment the

postcovid nice guidance

is very very sensible very pragmatic and

advocates rehabilitation so i think

there's lots to play out there

what will happen with the chronic

fatigue me once what will happen with

the nice ones

but you know i think we just have to we

just have to have this rehabilitation

because it's the only thing we've got

apart from time

absolutely that's that's wonderful thank

you so much for taking the time to speak

to us today that's very kind of you

thank you

great pleasure thank you very much

Sharpe lists support groups as one of the "social factors" that influence recovery -- included are Long Covid Support and ME Action's "Long Covid and ME - Understanding the connection" group.

He says that "At present the best treatment is psychologically informed rehabilitation", accompanied by slides showing improvement from GET and CBT in the PACE trial. Meanwhile, he puts the NICE ME/CFS draft guidelines under "Challenges in providing rehabilitation".

Admittedly, I didn't expect he would tell Paul Garner's story as a "Case study from the BMJ". But he did.

Trying to remember the paper where I first read this, I think it Wessley or White, but it was an older paper that highlighted financial gain (e.g. from disability) as well.

edit: So far, couldn't find the paper I was looking for, although this one (1992) by Sharpe. My bolding.

Functional impairment was significantly associated with belief in a viral cause of the illness (odds ratio = 3.9; 95% confidence interval 1.5 to 9.9), limiting exercise (3.2; 1.5 to 6.6), avoiding alcohol (4.5; 1.8 to 11.3), changing or leaving employment (3.1; 1.4 to 6.9), belonging to a self help organization (7.8; 2.5 to 23.9), and current emotional disorder (4.4; 2.0 to 9.3).

Alternatively, they may indicate factors that tend to maintain functional impairment. Thus membership of a patient organisation may be an understandable consequence of a more disabling illness or, alternatively, could be a marker of beliefs in physical causation and the need to limit activity which may perpetuate illness.

Telling, conclusion in Sharpe's own words, I wonder, if he is present the conclusion that support groups are dangerous, and his own conclusions are uncertain and opposite, that maybe did he mention both sides in the presentation or present evidence for his conclusion? As the paper above provides no evidence that they are a perpetuating factor.

Last edited:

Esther12

Senior Member (Voting Rights)

Just a couple of excerpts from Sharpe.

On PACE:

On Long Covid rehab:

On PACE:

this is the trial

that uh i did with colleagues about 10

years ago

in chronic fatigue syndrome and

basically different treatments were

tested you can see here smc

standard medical care gets graded

exercise

apt is pacing living within your limits

and cbt

cbt so basically they fall into the

the rehabilitative treatments those that

encourage

people with care to gradually build on

what they can do and not worry too much

about the consequences of that

that's the bottom two and the top two

are the ones the more conservative ones

just medical care

or live within your limits and you could

see there at 52 weeks in this

trial there was a clear greater

reduction in fatigue

perhaps paradoxically of those that had

the more active rehabilitation

and similar greater physical

function in those that had the more

active rehabilitation

and this idea of just pacing just

accepting your limits

is no better and possibly actually

slightly worse than nothing

than medical care so that has been

again some you may know immensely

controversial

because uh some of the patient groups

are very against this they feel it's um

it's harmful it's uh not validating

their illness

and so that leads to some potential

difficulties

for us in helping patients but i think

at the moment

if you've found and treated the obvious

things you can treat

the best approach to pros covid is

accepting it'll take time

and doing what i might call

psychologically informed robot

rehabilitation explicitly dealing with

worries

but helping them very gently return to

activity

so if rehabilitation is at the moment

our best hope what are the challenges in

providing that to our patients

well the obvious challenge is there

aren't many rehabilitation

multi-disciplinary teams as you could

see a picture of there

they're being set up certainly in some

places in the uk

with short-term funding um as we have in

oxford

On Long Covid rehab:

the complicating factor is that nice

who is the authority that

that recommends treatments is

potentially in a contrary position

they've done provisional guidelines on

the management of post covid

which are good guidelines uh i think

that they're they're not very specific

but they're very sound

but they're also doing guidelines on

any chronic fatigue syndrome which in

their current form

they're being revised in in the light of

feedback

are say you shouldn't have

rehabilitation and graded exercise

so i don't know how that's going to play

out but that may complicate the

provision of treatment

for postcovid patients

so what you really want to know is

okay there's all this stuff it's very

complicated and we rehabilitate

how well are people going to do how many

going to end up

from the swiss re perspective of having

chronic disability and chronic work

disability

and that's the one thing of course we

don't know because it hasn't been around

long enough

but i think our experiences to date

that most patients do do improve um

it may be slow we may be talking months

rather than weeks

but with some advice a bit of follow-up

most people do improve

so as far as we can see that approach of

getting people to have a sound

understanding

and not worry too much and work on

rehabilitation is helpful

in the absence of really good data um

physicians usually fall back as you know

on the rule of thirds

so my guess would be about a third these

people won't do so well

about a third will do very well and

about a third will be somewhere between

the two

and so if we say we've got five percent

and we

applies the rule of thirds a guess would

be

someone something like one percent of

these people may have some long-term

disability

uh that is a guess and it'll depend on

the care people get

but given the number of people with

covid that could potentially be quite a

lot of people