Murph

Senior Member (Voting Rights)

A better answer would be that having ME/CFS doesn't make one immune to deconditioning and deconditioning will contribute to some degree to how people are feeling.

The concept of deconditioning was abused to deny the existence of an underlying illness and the suffering of patients and that's why it's not popular among patients, but it's certainly occurring to some degree.

I agree with this, we will not be afforded the luxury of being immune to deconditioning. It's not the number one cause of our problems, not by a long shot. And even if it is there, doesn't mean doing exercise is worth it. The short-run symptom cost of exercising is for most people greater than the upside of exercising. Add in the risk of a drop in baseline and the risk of exercising becomes far greater than any upside from exercising for most pwme.

But it is there, in the background, meaning that even on the best, lowest-symptom day, we are going to have less capacity than before we got sick.

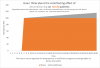

is this chart helpful?

I find benefit from exercising, from being stronger, and I think that's because of two factors in my me/cfs. 1. I'm mild. 2. POTS is a big issue for me. I suspect people for whom POTS is a tiny part of their symptom constellation are less likely to experience any upside from exercise.

I'd also make a strong argument that for anyone with even the faintest amount of POTS, walking is a super bad choice. it just shakes all the blood to your legs, and it doesn't do much to make you stronger. The famous Jen Brea story of decline is a story of walking too far. Everyone perceives walking as the most gentle exercise, its the go-to for the sickly and faint, but my feeling is its kryptonite for anyone whose mecfs includes pots.

The controversial extension of this observation is that there are probably higher and lower risk types of exercise. If I had to guess at what is lowest risk it would be brief bursts of strength exercise on small muscles, that terminate well below threshold and are done sitting down/recumbent. bicep curls a good example.

One idea I sometimes consider is that pacing is to mecfs what the banana diet was to coeliac disease. It helps enormously but we haven't grasped why. When we zero in on why pacing is so good, and why aggressive rest can sometimes even lead to a lift in baseline, then we might actually be able to define higher and lower risk types of exercise with precision. Until then we're splashing round in ignorance and exercise is very risky.

Last edited: