ryanc97

Senior Member (Voting Rights)

If we're talking about averages, it has to be about the whole group. Otherwise, it would be cherrypicking - the same as if we found one person in the Rituximab study with a 5000 step count increase, called them a responder, and were comparing to that.

From Dara trial:

So average increase of 2503 steps at 8-9 months.

@forestglip

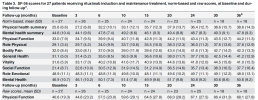

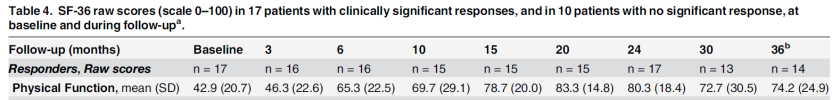

Pooling response by survey/SF36 data:

Responders in P3/Dara:

Average responder P3 n=46: 1k - 2.2k to 3.2k.

Average responder Dara n=6: 4k- 3k to 7k.

Non responders in P3/Dara:

Average stable symptoms P3 n=90: 1.5k - 2k to 3.5k

Avreage worsening symptoms P3 n=15: 0.6k - 1.8k to 2.4k

Average non responder Dara n=4: 0 - 3k to 3k

------------------------------------

In ritux P3, step effect does not correlate with SF36 response. In Dara, step effect correlates with SF36 response quite well.

Surveys like SF36 are breeding grounds for placebo effects, step counts are not.

Last edited: