The effects of exercise on dynamic sleep morphology in healthy controls and patients with chronic fatigue syndrome

Akifumi Kishi, Fumiharu Togo, Dane B Cook, Marc Klapholz, Yoshiharu Yamamoto, David M Rapoport, Benjamin H Natelson

Published: 2013

(Line breaks added)

Abstract

Effects of exercise on dynamic aspects of sleep have not been studied. We hypothesized exercise altered dynamic sleep morphology differently for healthy controls relative to chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) patients.

Sixteen controls (38 ± 9 years) and 17 CFS patients (41 ± 8 years) underwent polysomnography on baseline nights and nights after maximal exercise testing. We calculated transition probabilities and rates (as a measure of relative and temporal transition frequency, respectively) between sleep stages and cumulative duration distributions (as a measure of continuity) of each sleep stage and sleep as a whole.

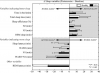

After exercise, controls showed a significantly greater probability of transition from N1 to N2 and a lower rate of transition from N1 to wake than at baseline; CFS showed a significantly greater probability of transition from N2 to N3 and a lower rate of transition from N2 to N1. These findings suggest improved quality of sleep after exercise.

After exercise, controls had improved sleep continuity, whereas CFS had less continuous N1 and more continuous rapid eye movement (REM) sleep. However, CFS had a significantly greater probability and rate of transition from REM to wake than controls. Probability of transition from REM to wake correlated significantly with increases in subjective fatigue, pain, and sleepiness overnight in CFS – suggesting these transitions may relate to patient complaints of unrefreshing sleep.

Thus, exercise promoted transitions to deeper sleep stages and inhibited transitions to lighter sleep stages for controls and CFS, but CFS also reported increased fatigue and continued to have REM sleep disruption. This dissociation suggests possible mechanistic pathways for the underlying pathology of CFS.

Link | PDF (Physiological Reports) [Open Access]

Akifumi Kishi, Fumiharu Togo, Dane B Cook, Marc Klapholz, Yoshiharu Yamamoto, David M Rapoport, Benjamin H Natelson

Published: 2013

(Line breaks added)

Abstract

Effects of exercise on dynamic aspects of sleep have not been studied. We hypothesized exercise altered dynamic sleep morphology differently for healthy controls relative to chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) patients.

Sixteen controls (38 ± 9 years) and 17 CFS patients (41 ± 8 years) underwent polysomnography on baseline nights and nights after maximal exercise testing. We calculated transition probabilities and rates (as a measure of relative and temporal transition frequency, respectively) between sleep stages and cumulative duration distributions (as a measure of continuity) of each sleep stage and sleep as a whole.

After exercise, controls showed a significantly greater probability of transition from N1 to N2 and a lower rate of transition from N1 to wake than at baseline; CFS showed a significantly greater probability of transition from N2 to N3 and a lower rate of transition from N2 to N1. These findings suggest improved quality of sleep after exercise.

After exercise, controls had improved sleep continuity, whereas CFS had less continuous N1 and more continuous rapid eye movement (REM) sleep. However, CFS had a significantly greater probability and rate of transition from REM to wake than controls. Probability of transition from REM to wake correlated significantly with increases in subjective fatigue, pain, and sleepiness overnight in CFS – suggesting these transitions may relate to patient complaints of unrefreshing sleep.

Thus, exercise promoted transitions to deeper sleep stages and inhibited transitions to lighter sleep stages for controls and CFS, but CFS also reported increased fatigue and continued to have REM sleep disruption. This dissociation suggests possible mechanistic pathways for the underlying pathology of CFS.

Link | PDF (Physiological Reports) [Open Access]