Diagnosing CFS

Diagnostic Challenges

Diagnosing CFS can be challenging for healthcare professionals. A number of factors adds to the complexity of making a CFS diagnosis: (1) there is no diagnostic laboratory test or biomarker for CFS; (2) fatigue and other symptoms of CFS are common to many illnesses; (3) many people with CFS do not look sick in spite of their profound disability; (4) symptoms vary from person to person in type, number, and severity; and (5) symptoms may vary in an individual patient over time.

These factors have contributed to an alarmingly low diagnosis rate. Of the 4 million Americans who have CFS,[4] more than 80% have not been diagnosed yet.[5,6] There is evidence to suggest that the longer a person is ill before a diagnosis, the more complicated the course of the illness appears to be, making early detection and treatment of CFS of utmost importance.[1]

Diagnosing CFS

To be diagnosed with CFS, patients must experience significant reduction in their previous ability to perform one or more aspects of daily life (work, household, recreation, or school). And, by definition, all people suffering with CFS experience severe, all-encompassing mental and physical fatigue that is not relieved by rest and that has lasted longer than 6 months. The fatigue is accompanied by characteristic symptoms that may be more bothersome to the patients than the fatigue itself.

Clinicians should consider a diagnosis of CFS if these 2 criteria are met:

1. Unexplained, persistent fatigue that is not due to ongoing exertion, is not substantially relieved by rest, is of new onset (not lifelong), and results in a significant reduction in previous levels of activity.

2. Four or more of the following symptoms are present for 6 months or more:

- Impaired memory or concentration

- Postexertional malaise (extreme, prolonged exhaustion and exacerbation of symptoms following physical or mental exertion)

- Unrefreshing sleep

- Muscle pain

- Multijoint pain without swelling or redness

- Headaches of a new type or severity

- Sore throat that is frequent or recurring

- Tender cervical or axillary lymph nodes

Diagnostic Model

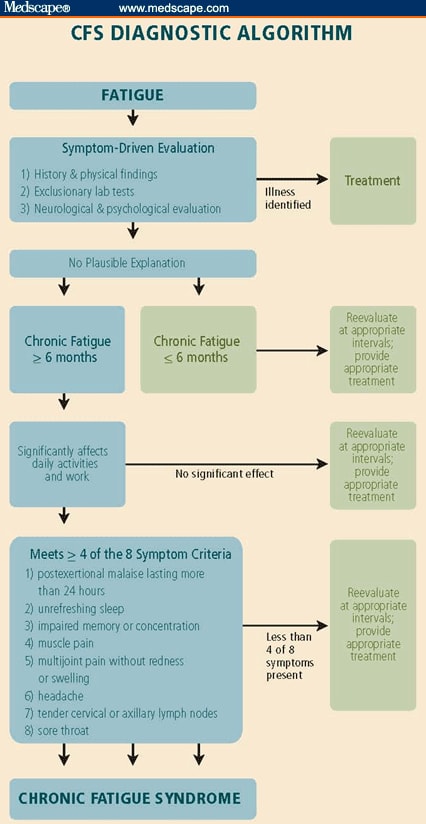

The decision-making model (Figure) is based on the International Case Definition,[18] which forms the basis for a reliable diagnostic algorithm for CFS, particularly in adults.[19] Developed by 2 physicians who have treated hundreds of CFS patients, this model guides clinical assessment of patients presenting with CFS symptoms, and it provides a stepwise approach to making the diagnosis.

Figure. CFS diagnostic algorithm.

CFS occurs in children and adolescents, though less frequently in children younger than 11 years.[8,20] Pediatric CFS often leads to frequent school absences, a decline in academic performance, and a severe decrease in extracurricular activities. It is not uncommon for pediatric CFS to be misdiagnosed as school phobia, anxiety disorder or depression, or as a manifestation of severe family dysfunction, leading to underdiagnosis of the illness and inappropriate treatment. Two tools have been developed recently to help assess CFS in children: a pediatric case definition and the DePaul Pediatric Health Questionnaire.[21]

Other Symptoms

CFS patients often experience symptoms that are not diagnostic but that may contribute to overall morbidity.[22] These can include allergies, asthma, and sinus problems; loss of thermostatic stability (chills and night sweats, subnormal body temperature, intolerance of extreme heat or cold); transient numbness, tingling, or burning sensations in the face or extremities; lightheadedness, dizziness, balance problems, difficulty retaining upright posture (orthostatic instability), palpitations, or arrhythmias; irritable bowel, nausea, or abdominal pain; marked weight changes; psychological problems such as irritability, mood swings, depressed mood, anxiety, and panic attacks; sensitivity to medications, foods, chemicals, or odors; visual problems such as blurred vision, dry eyes, and photophobia; gynecologic problems such as PMS, vulvodynia, and endometriosis; and brain fog (word-finding difficulties, inability to comprehend/retain what is read, confusion, or disorientation).

Clinicians should remain alert to the development of these symptoms and treat them with commonly accepted modalities to reduce the illness burden on patients.

Clinical Evaluation

When the CFS criteria are met, health professionals need to exclude other illnesses before a diagnosis can be confirmed. Because there is no diagnostic lab test for CFS, it is a diagnosis of exclusion.

CFS patients tend to present in 2 distinct ways -- acute onset or gradual onset over a period of a few months. When patients don't recover from an initial acute infection or flu-like illness in the usual time and present with CFS-like symptoms 6 or more months later, clinicians will want to consider postviral CFS as a diagnosis.

Clinical evaluation of patients with a fatiguing illness requires:

- A detailed patient history, including a review of medications that could cause fatigue;

- A thorough physical examination;

- A mental status screening; and

- A minimum battery of laboratory screening tests.

Recommended tests include:

- Urinalysis

- Total protein

- Glucose

- C-reactive protein

- Phosphorus

- Electrolytes

- Complete blood count (CBC) with leukocyte differential

- Alkaline phosphatase (ALP)

- Creatinine

- Blood urea nitrogen (BUN)

- Albumin

- Globulin

- Calcium

- Alanine aminotransferase (ALT) or aspartate transaminase serum level (AST)

- Thyroid function tests (TSH and free T4)

- ANA and rheumatoid factor (if indicated)

- Lyme serology (if indicated)

These tests are useful in excluding other possible causes for symptoms. Normal results may be enough to exclude other illnesses and to then diagnose CFS. However, in some cases, further tests or referral to specialists may be indicated to confirm or exclude a diagnosis that better explains the fatigue state or to follow up on results of the initial screening tests.

There are several questionnaires that can assist with the identification and monitoring of CFS patients. These include the MOS SF-36,[23] Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory,[24] the McGill Pain Questionnaire,[25] Bell's Disability Scale,[26] Subjective Functional Capacity Assessment,[27] Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index,[28] and the CDC Symptom Inventory.[29]

Comorbid Conditions

It is not uncommon for CFS patients to present with symptoms of other illnesses, and some patients actually receive diagnoses for multiple conditions. Sleep disorders, metabolic syndrome, mood disorders, focal pain conditions, orthostatic intolerance, gastrointestinal disorders, allergies, and asthma are common comorbid conditions. Clinicians should aggressively identify and treat these conditions because they contribute to the symptom burden and make managing CFS more difficult.

Diagnosis can also be complicated by medically unexplained clinical conditions that commonly overlap with CFS. Because many of these conditions lack a diagnostic test or biomarker and share symptoms such as fatigue and pain with CFS, unraveling which illnesses are present can be difficult. Comorbid conditions that clinicians should be alert for include fibromyalgia, irritable bowel syndrome, multiple chemical sensitivity, Gulf War syndrome, temporomandibular joint disorder, and overactive bladder or interstitial cystitis. Fibromyalgia appears to be the most common medically unexplained overlapping condition with CFS. Research suggests that 35% to 70% of CFS patients also have fibromyalgia,[30] so it is helpful for clinicians treating CFS patients to be familiar with diagnostic and treatment practices for both illnesses.

Exclusionary Conditions

CFS can resemble many other disorders, including mononucleosis, Lyme disease, lupus, multiple sclerosis, primary sleep disorders like narcolepsy or sleep apnea, hypothyroidism, severe obesity, and major depressive disorders. All these conditions must be considered and, if present, receive appropriate treatment. Medications can also cause side effects that mimic the symptoms of CFS.

.

.