Variation in Repeated Handgrip Strength Testing Indicates Submaximal Force Production in Patients With Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome

Stoyan Popkirov

Background

Changes in handgrip strength have recently been adapted as clinical biomarkers for myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) under the assumption of a disease-specific peripheral neuromuscular dysfunction. However, some have proposed that strength impairments in ME/CFS are better explained by alterations in higher-order motor control. In serial measurements, exertion can been assessed through analysis of variation, since maximal voluntary contractions exhibit lower coefficients of variation (CV) than submaximal contractions.

Methods

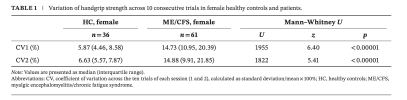

Serial handgrip strength measurements of 105 ME/CFS patients and 66 healthy controls from a previously published biomarker validation study are analyzed post hoc regarding their CV. CV is separately compared in a subsample of participant with normal indexes of fatigability.

Results

Compared to healthy controls, patients had significantly higher CV, largely over the conservative 15% cutoff associated with submaximal exertion. In the subsample of study participants, whose within-session fatigability was within normal bounds, CV was still significantly higher in female patients; the difference in male patients was not statistically significant (p = 0.06).

Conclusions

This analysis suggests that loss of grip strength is likely compounded by alterations in higher-order motor control, challenging its utility as a biomarker of peripheral dysfunction. Functional weakness is discussed within a framework that sees motor fatigue as a result of reduced implicit self-efficacy acquired in the context of chronic dyshomoeostasis and disability.

Web | PDF | European Journal of Neurology | Open Access

Stoyan Popkirov

Background

Changes in handgrip strength have recently been adapted as clinical biomarkers for myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) under the assumption of a disease-specific peripheral neuromuscular dysfunction. However, some have proposed that strength impairments in ME/CFS are better explained by alterations in higher-order motor control. In serial measurements, exertion can been assessed through analysis of variation, since maximal voluntary contractions exhibit lower coefficients of variation (CV) than submaximal contractions.

Methods

Serial handgrip strength measurements of 105 ME/CFS patients and 66 healthy controls from a previously published biomarker validation study are analyzed post hoc regarding their CV. CV is separately compared in a subsample of participant with normal indexes of fatigability.

Results

Compared to healthy controls, patients had significantly higher CV, largely over the conservative 15% cutoff associated with submaximal exertion. In the subsample of study participants, whose within-session fatigability was within normal bounds, CV was still significantly higher in female patients; the difference in male patients was not statistically significant (p = 0.06).

Conclusions

This analysis suggests that loss of grip strength is likely compounded by alterations in higher-order motor control, challenging its utility as a biomarker of peripheral dysfunction. Functional weakness is discussed within a framework that sees motor fatigue as a result of reduced implicit self-efficacy acquired in the context of chronic dyshomoeostasis and disability.

Web | PDF | European Journal of Neurology | Open Access