A 2007 amendment to the Mental Health Act called for advance wishes to be “respected”. However, it also ditched a requirement for disorders justifying detention to be “treatable”, introducing an arguably less therapeutically minded, more risk-averse “appropriate” test instead.

If two doctors diagnose that you have a mental health disorder (e.g. depression, bipolar disorder) and deem that you need to be treated for it to protect you or the public from your possible future actions, the choice and course of treatment is ultimately, lawfully, out of your hands as a patient.

Under the Mental Health Act in its current form, you can record advance treatment wishes before you’re hospitalised. But all advance treatment refusals other than neurosurgery can be overridden if deemed ‘appropriate’ by clinicians.

Should advance refusals of ECT become binding under the new Mental Health Act?

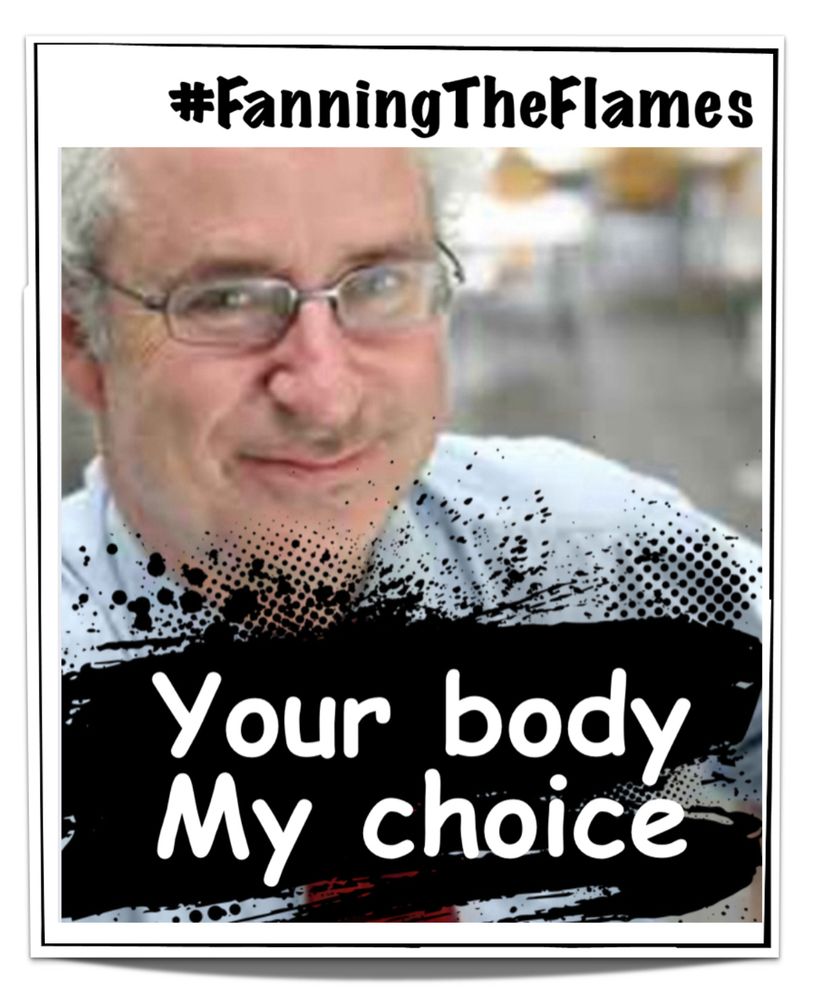

Wessely believes there remains a role for ECT in mental health care.

“In my advance directive, I’ve said if I get old and get very severe melancholic depression, I would like ECT,” the psychiatrist told MHT, speaking after a recent London workshop for the new Act.

Earlier in the day, review vice-chair and suicide survivor Steve Gilbert referenced the “life-saving” qualities of ECT during a group discussion on advance statements.

Mental Health Today asked Wessely to describe how ECT, which comprises induced brain seizures, contribute to improved mental health.

ECT has its backers. But what are its tangible therapeutic qualities?

“Have you ever seen anyone suffering from catatonia or depressive stupor?”

“These are some of the most severe forms of mental illness we have.”

“These are people who have stopped speaking, who have stopped eating or drinking, and who – in the old days – died. They died of starvation. There was no treatment available. You couldn’t feed them. It wasn’t possible. And they died. And it’s a really very unpleasant death.”

“That happened in the era before psychotro… [tails off, but presumably was going to say psychotropics] before we had promazine [an antipsychotic]… and before we had the ability to do nutrition and before we had ECT.”

“That was quite a common occurrence in mental hospitals. We don’t see those illnesses half as commonly now as we used to, thank god, but they are still around. They haven’t gone away.”