bicentennial

Senior Member (Voting Rights)

Blog Summary .... audio of summary also available at link

full blog:

when the body's alarm wont turn OFF

The finding is when alarmed ... not ... why alarmed

I agree with people who say the immune system is both under-active and over-active. This was indicated in Dr Komaroff's study, detailing the immune findings in ME and CFS, and Long Covid

Dr Komaroff also indicated, supposed or surmised something to do with the danger response of an entity (organism) informed by cellular response to danger, or vice versa it got a bit complex and I'm a bit vague on this. But I'm sure research didn't finish interpreting this edgy immunity, which:

- reacted more strongly to microbial “danger signals” than in healthy controls, even before exercise

- after activity, some responses looked blunted, suggesting a system that is both over-reactive and easily exhausted.

I went to looksee how these microbial danger signals could be induced. It was by:

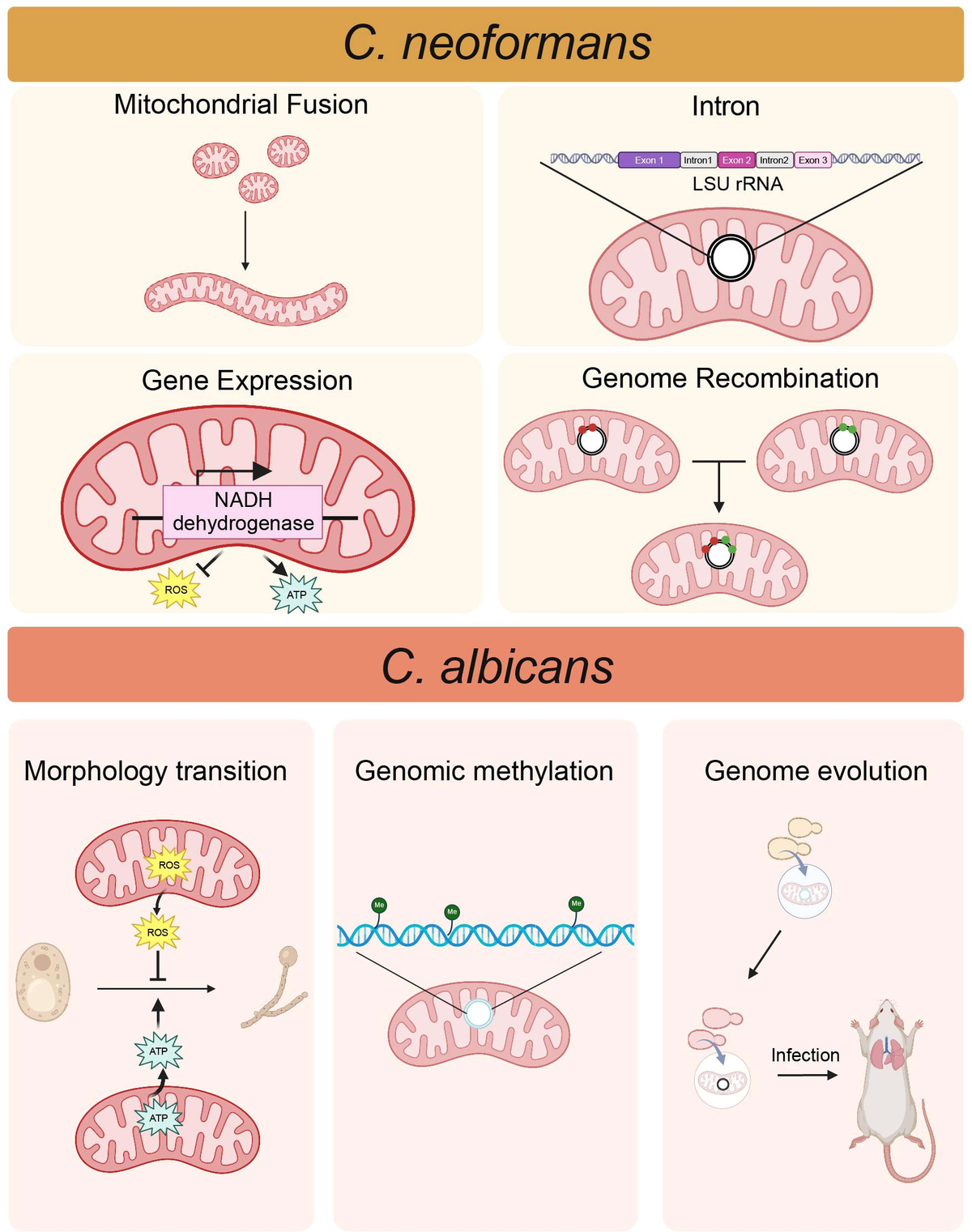

- testing how immune cells responded when exposed to simulated microbial threats, such as bacterial toxins, viral RNA mimics, and fragments of yeast cells

I am trying to imagine a culture watching some isolated immune cells react to some pathogenic materials. OK, so the healthy control's immune cells reacted within some norm.

The results, taken together, suggest

an immune system that’s hypersensitive to danger signals,

a metabolism struggling to generate clean energy, and

a gut-tissue barrier that may be letting inflammatory sparks fly.

Crucially, many of these abnormalities worsened after exercise and tracked with symptom severity.

Yes, well, it mostly fits, but I want to disagree with the assumption or presumption of hypersensitivity. The finding is when ... not ... why ... alarmed.

If a body became more susceptible to pathogens then the extra reaction is in proportion and not hypersensitive at all, nor sensitised, and maybe better not to dampen it down instead of shoring up susceptibility. If already infested, immunity was worn down, wobbly, for a long time

Also informing my suspicion is the fact that I no longer believe my body is at fault. Possibly my body is very rational and proportionate, after all that. Or I am up the creek with no paddle here

Then I have a question about the metabolism which I think is not only "energy use"...