As the above response suggests that the quotation may have a wider significance it is probably best for the paragraph to be quoted in full, since the original is not widely available and I would not wish to be accused of unreasonable selective quoting.

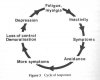

"The link between physical activity and well-being has been studied extensively. Hughes et al (1984) found a correlation between fatigue and physical inactivity independent of physical health and fitness, whilst Stephens (1988) concluded that the positive correlation between physical activity, better mental health and lower levels of anxiety and depression (and hence fatigue) occurred independently of physical health status. In an eight-year follow-up study of nearly 200 healthy adults it was shown that lack of activity was independently associated with a two-fold increase in the risk of depressive illness (Farmer et al 1988). Looking at coping strategies, Montgomery,(1983) studied fatigue in a student population. He found significant differences in response to the question "when tired, what do you typically do?". For tired subjects the sensations of fatigue serve as stimulus to reduce their level of activity, acting as a cue to slow down or stop, whilst non-tired subjects tend to ignore similar sensation. Finally, in pain patients' rest is a potent reinforcer of both symptoms and disability (Keefe and Gil, 1986). Inactivity can, and does, cause fatigue. Nevertheless, with the occasional exception (Edwards, 1986; Dobkin,1989), patients with PVFS are usually told from a variety of sources that lack of activity is invariably and permanently a consequence of fatigue. Such advice may be both inaccurate and counterproductive, and may serve to perpetuate the very disability that it is intended to minimise.

………....Any suggestion that the explanations advanced in this chapter seek to blame the patient for his or her predicament are without foundation."

"The link between physical activity and well-being has been studied extensively. Hughes et al (1984) found a correlation between fatigue and physical inactivity independent of physical health and fitness, whilst Stephens (1988) concluded that the positive correlation between physical activity, better mental health and lower levels of anxiety and depression (and hence fatigue) occurred independently of physical health status. In an eight-year follow-up study of nearly 200 healthy adults it was shown that lack of activity was independently associated with a two-fold increase in the risk of depressive illness (Farmer et al 1988). Looking at coping strategies, Montgomery,(1983) studied fatigue in a student population. He found significant differences in response to the question "when tired, what do you typically do?". For tired subjects the sensations of fatigue serve as stimulus to reduce their level of activity, acting as a cue to slow down or stop, whilst non-tired subjects tend to ignore similar sensation. Finally, in pain patients' rest is a potent reinforcer of both symptoms and disability (Keefe and Gil, 1986). Inactivity can, and does, cause fatigue. Nevertheless, with the occasional exception (Edwards, 1986; Dobkin,1989), patients with PVFS are usually told from a variety of sources that lack of activity is invariably and permanently a consequence of fatigue. Such advice may be both inaccurate and counterproductive, and may serve to perpetuate the very disability that it is intended to minimise.

………....Any suggestion that the explanations advanced in this chapter seek to blame the patient for his or her predicament are without foundation."